Dear Shaded Viewers,

I was introduced to Mari Bastashevski through my friend Alex Murray-Leslie and was immediately drawn into her work. We passed some time together during the summer chatting at Cafe Flore and walking through Paris.

The following interview is the result of our conversations in Paris.

What is your philosophy on life and love?

The U-Bahn window sign that says “please leave me open”.

What’s your latest theory?

The feral children theory! It’s about the significance of encounters with strangers that we recognise from our past and future lives. Lives in which we went around the forest looking for foxes, poking the earth with sticks, gathering mushrooms. Don’t get me wrong, the theory isn’t about rekindling contact with nature, avoiding the labour of conventional relationships, or the nostalgia for any special age. Infantilism is abhorrent and unnecessary; each age has its own innocence. It also isn’t about any specific configuration of love, desire, or friendship, but rather about allowing the ancient and reincarnated versions of ourselves to find one another in the dark, deep, ocean of noise, over and over again.

In your extensive research on the role of new technology and social media- can you give a brief description on your findings?

In Technics and Time Bernard Stiegler points out that during the industrial revolution the pace of technological progress has never surpassed the collective limitations of a body and the ecological limitations of our planet. One major difference between industrial and cognitive capitalism is that this limit is no longer in place. The delicate balance has shifted in favor of the algorithm. It’s a feedback loop in which an ecology, as well as the body, is considered a resource for the expansion of the network (which still depends on it infrastructurally) This, in turn, gives rise to new appetites and new forms of industry, a new eco-industrial-systems.

Momentary blackout events like the one that took place on Monday October 4th made visible the extent to which these eco-industrial systems are monopolised and co-dependent, as well as the glance into how people were not so secretly hoping it would never come back. As micro-influence goes, I still think decisions about how and what we do online matter.

I call this process gestures of potentiality, something I tried to unpack in my text for EastEast.

Currently one of your projects is working on the relationship between snails, humans and technology, and I imagine as well the relationship between animals, humans and technology. How long has this study been going on and what are your findings to date, overall?

It’s a work that draws on the London Natural History Museum Archive’s drawers of formally uncatalogued gastropods. The Museum is a home to one of the largest collections of animal remains on earth. Millions are still uncatalogued. Some of the drawers to which they are consigned for eternity have not been opened in two hundred years. I decided to make a microcosm where the species are freed from drawers and exist in a certain way before they leave us. The work has become an interdisciplinary experiment, collaborating across architecture, philosophy, and ethology. Defining the way the microcosm was going to work is where we encountered the most philosophical problems (ha ha) I wanted to speculate a world together with other-than-humans, and after much deliberated we’ve decided to work with living animals. That’s a first. We have since built them an app on which they make music and sketches. It’s and-alone software used by a rout of snails from Switzerland, Netherlands, Us, and Norway.

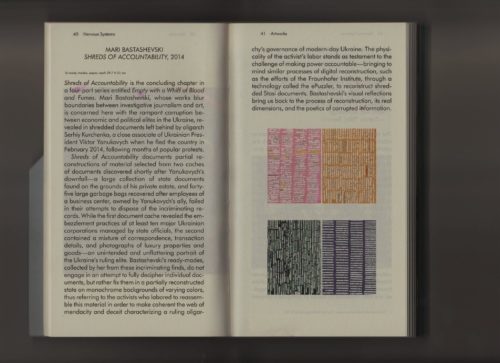

Can you tell me about ‘State Business’ and ‘Empty with a whiff of blood and fumes’? Does working on a project like that put you in any kind of danger? How do you obtain access to documentation and photographs?

Both projects explore the role of visual media narrative in perpetuating certain ideas about states, companies, conflicts, and ideologies.

State Business is a six chapter long case study, where each chapter reconstructs a conflict narrative by tracing a trajectory of a specific transaction that eventually resulted in very real casualties without a culprit.

Empty With a Whiff of Blood and Fumes’ is a headline borrowed from a local newspaper that ran this headline the day after the first casualty of the 2014 Maidan Revolution was recorded. This work examines why people still believe in the significance of gathering historic and cultural evidence, it’s about the irrational faith in the rule of law, the need for governance, as the tide turns full circle between autocrat-revolution-war-autocrats.

Gaining access is easy. It has always been something of my curse. I don’t really have a tradecraft methodology. I was curious, I might have engineered my way around loopholes, but I’ve never broken any laws. Sometimes it was as simple as walking through the front door. It took six months to figure out how to get inside Verint HQ in Israel, but eventually I contacted the interior designer who designed their office and asked him for a tour of high tech offices in Tel Aviv. He brought me along and as soon as I said I was an artist. No one asked me for anything other than a date (no thank you, Nathan). Was this dangerous? Probably. I honestly don’t know. I came of age amidst the 90s post soviet chaos so I’ve never been shielded from violence and systemic injustice to begin with. The work itself was never meant to enter into a conflict with anyone specific. It’s about the image of politics, but it is far less ‘political’ than it appears to be.

What got you so interested in surveillance? How are these technologies used against individuals and groups like journalists?

What got me interested in surveillance was getting hired as a consultant to do sleuthing for a counter-surveillance non-profit that worked to push back against the surveillance legislation mushrooming in the wake of 9/11. The way these technologies are used is pretty wild; the wildest thing of all is the extent to which the business of surveillance cuts beyond and across all ideologies; for example, how quickly Israeli spyware penetrated all the markets in the Middle East. No less wild is the counter-surveillance framework for methodical paranoia, all theories of creative camouflage, and widespread advocacy for permanent, on-principle encryption. The conversation about surveillance is stalled in the very same militarised subjectivity it aims to oppose. I find the argument that gaining access to the military machines of counter-surveillance a civilian can undermine necro-corporate-state power is a bit tired. It also neglects to take into account that technology, too, is capable of subverting the civilian.

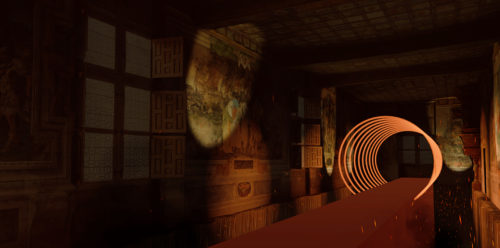

Let’s talk about VR and ‘Terra Incognita’ installation at Chateau d’Oiron. How do you transmit your crystal ball into the future? The true immersive experience can only happen by actually walking through the virtual material, can you explain how one is guided through the space and what they will encounter and in the process creating such a world.

The Chateau is a French cultural heritage site and a home to an incredibly well-preserved collection of historic artifacts, puzzlingly complex architecture, and an evolving collection of site specific contemporary art. ‘Terra Incognita’ is a site-specific VR installation set in one of its halls, La Galerie du Grand Ecuyer, a room I reconfigure and reinterpret into a message left by an unknown sentient form for future alien visitors. It is a cipher that is intended for a lifeform that may or may not be human. It is a message from the future, for the future, about a future-past that may still come to pass.

The work is made at a 1:1 scale, and the viewer is invited to walk into the virtual-material crossover. The viewer is accompanied by a guardian who exists memetically in both material and virtual form. The project is my first VR work (made in collaboration with a brilliant coder and an NYC-based artist, Laura Juo-Hsin Chen).

Initially, Carine Guimbard, a curator at the time, invited me to the Chateau to show some existing works, but I needed a break from it and didn’t think it was a good fit. I asked Carine whether I could do something else instead, something entirely different and site-specific. It turned out to be possible. The year I’ve ended up spending working in and around the Chateau was a seismic one.

Opening only a week before the first wave of Covid, Terra Incognita was alarmingly prescient. The future I’ve anticipated thousand years from now, was but a week away.

Little by little, as the oxygen became scarce, logosexuals stopped spending air on words. And, as the uses of language diminished, they resorted to gestures, sighing, and touch. The human period was succeeded by the light age of silence.