Hans Ulrich Obrist is a curator, critic, interviewer, writer, and director of the Serpentine Gallery in London. He is an ubermensch of the art world known for his massive contributions to artistic institutions all around the world, and he started when he was barely a teenager. If you don’t know who he is, think again and you probably do.

It’s 11:30 a.m. on a Tuesday, and Hans Ulrich Obrist is on the move. We had intended to meet at Cafe de Flore where Obrist often likes to have press interviews, but instead we are meeting in between his many appointments, in a taxi parked outside the Louvre. It’s gray and rainy in Paris. Obrist is wearing a black trench coat over a crisp white button down, black trousers, shiny black kiltie loafers, two phones in one hand, and a compact leather backpack on his lap. My heels are soaked.

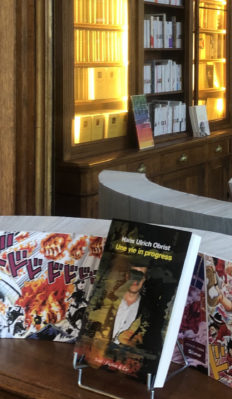

On the occasion of his most recent book release, Une Vie In Progress (A Life in Progress), the Pharmacie des Âmes held a book signing and conversation with Obrist and Ramdane Touhami earlier this month. I got there early and overheard Touhami say to a colleague, “I met with Hans at six o’clock this morning! As usual!” The cozy bookstore sits on a quiet street in the 7th arrondissement, but people are squished inside like tinned fish and spilling out the front door to listen to him speak. Obrist immediately and passionately dives into a story about some other artist’s project and Touhami has to remind him many times, “We are here to talk about you, you, you!” But, I think that Obrist’s identity is the culmination of the works and ideas of others; he exists as a metaphysical bridge between artists and art-spaces, and as the sum of their meeting.

Pushed by his editor to write this book during lockdown in London, the curator and critic has finally taken the opportunity to step into the limelight. This is perhaps the only introspective COVID project that I am interested in. I want to ask him one hundred questions, but Rue de Rivoli to Rue de Turennes is only a 20-minute car ride and as usual, Obrist has a wonderful lot to say.

—

Rianna Murray: I came to your book signing at the Pharmacie des Âmes. I didn’t get a copy though, because I was under the impression that it’s not yet been published in English?

Hans Ulrich Obrist: No, it hasn’t. It’s just in French for now.

RM: Do you plan on publishing in other languages?

HUO: Yeah, there is interest from several publishers. It’s definitely going to be translated, but I might also write a little bit more and adapt it because I always think that books in different languages have to be different. I don’t believe it’s a very homogenized idea that we throw the exact same books out in different languages.

Also, I’m Swiss. I grew up with French, Italian, and German and then I learned Spanish and English. These are all languages I can write. For me, if it’s a translation, I want to rework it for the English one, and also for the German one, and so on. So it’s going to come out, but in different versions.

RM: Right, I see. I think translation is definitely an art.

Actually, I’m glad that we have the chance to meet in person because I reread my initial questions for you and I had the time to look through more of your interviews, and I realized that everybody asks you the same things!

HUO: That’s always the thing, it’s so interesting that there’s a certain type of question that always comes back.

RM: I thought I was really clever asking what your unrealized projects are, but then I realized that’s what everyone asks!

*Obrist’s favorite question is to ask an artist about their unfinished/unrealized projects.

HUO: That question has been asked quite a lot, but there’s such a long list as a curator, sometimes like an architect. I would say that I can easily answer it differently each time. Because obviously, the answer I always give is that I want to do an exhibition on unrealized projects.

Because I’ve gathered so many and I have so many, but it’s ironic that whenever I want to do this show, it remains unrealized, something always falls through. One day I’m definitely going to do it. Then I have this other main project which is unrealized; I really want to start a new Black Mountain College. It was this amazing school in the 50s in the United States where you had scientists like Einstein and then also architects like Buckminster Fuller. I spoke a lot actually to Susan Weil, who was a student there and now in her eighties, a great artist. Rauschenberg studied there also, of course. It was fascinating to find out about this school where people from all different disciplines would teach. In art you also need to connect to science, to music, to literature. So, I dream of founding a school like Black Mountain College. But also, a lot of people no longer really want to teach, which is a great pity. We need to transmit to the future generation, as well as learn from them. It’s not a one-way thing. It’s both.

I used to teach in the early 2000s in Venice, and we brought the architecture department and the art department together. That was a huge success because the art students started working with the architecture students and everybody got really enthusiastic and learned from each other, and then the university lost the funding and since then I haven’t really been doing that. That’s my big unrealized project.

RM: Where would your school be?

HUO: Wherever we find the funding.

RM: Maybe in Paris? The Obrist Institute.

HUO: Yeah, it would be an institute!

RM: I’m curious- as a curator and an interviewer, one would assume that your role is more behind the curtain so-to-speak, but you have so much notoriety, you know, you’re quite a well known man! I’m wondering if the context of celebrity is ever limiting in those roles?

HUO: I mean, celebrity is very relative. My work might be well known in the art world, maybe in the world of culture, but there are still lots of fields where it wouldn’t necessarily be known. I always wanted to build bridges. It’s less about celebrity, but you’re right, of course, it’s public. My work has always been public.

I started by doing this very intimate show in my kitchen, but then quite soon, when I was in my early twenties I started to work with Kasper König who was my mentor, and so then already when I was like 23 it was quite public. And you know, I always had these kinds of public aspects, because I always wanted to build bridges. My aim is to bring worlds together. I want to connect art with society- it is a work of communication. It’s not necessarily about celebrity, it’s more about making things public and creating lots of different bridges in society. The role of the curator is the role of a very public junction maker. I build junctions and bring people together, bring artworks together, things like that.

Now we’re working on a show in Manchester about football with Juan Mata. I’m co-curating. We bring the world of art and football together. I work a lot on video games right now because a third of the world’s population engages with video games. At the Serpentine, our technology department is working on a video project with Gabriel Masan.

RM: And you’re doing a show at the Pompidou Metz?

HUO: Then at Pompidou-Metz, exactly. I’m curating a show there coming from Dusseldorf. It’s a touring show we did with JSC and now with Chiara Parisi, which will be of about 40 artists of the younger generation who all work with video games. I’m very interested right now in how video games become a platform of experimentation and that’s, again, bringing worlds together. I bring the world of art and video games together.

RM: I’m kind of anti-video game, I feel like it’s not art, like it’s not a valuable or lasting medium or context or something, but I guess that it is…There are probably a lot of people who feel the same way as I do?

HUO: A third of the population is engaging with video games. Millions of people, but then at the same time, you’re right, that also of course, a lot of it is of limited interest because it’s very commercial. I think it’s interesting right now that a lot of artists are actually inventing a very different way of approaching video games.

I hope you will find it interesting, as well as people who haven’t so far been interested in video games. We find it interesting. I was never really into video games before this.

RM: What was the catalyst that sparked this interest?

HUO: I always go to artist studios. I look and look, and I listen and then after about a year, like two years ago, every second studio visit I made, artists were saying they dream of doing a video game! During COVID time. It’s your generation of artists. Twenties and thirties, I would say. Millennial and younger.

RM: When does the show open?

HUO: It opens in June. You should come and see it.

RM: I will come and cover it for ASVOF!

I’d like to ask you about the accident you were in as a young boy. You’ve cited that incident as being what instilled in you this sort of remarkable lust for life. I’m curious, do you think that stems more from a fear of dying or an excitement to live? Maybe they are kind of the same thing.

HUO: Well, that’s an interesting question. It was almost like a wake-up call for me, because I grew up in a rather quiet town, a little town in Switzerland, and not much happened there. Then all of a sudden I had this near-death experience and I started to feel an urgency to do something in life-

RM: At seven?

HUO: I would say, yeah, in a way, it prompted that. Otherwise, that wouldn’t have happened at seven, I suppose.

I couldn’t do simple things, like for a year, and then it was all fine again, but I was just ill. And what do you do? I mean, ultimately you can’t really leave the house. I started to really get into books, and I asked my parents to buy lots of books and literature. It was the transition from children’s books into literature, right, because it was a bit early, but then that got me hooked on books. Then in my early teens, I read a lot of actual literature.

RM: The image people have of you is sort of non-stop and everywhere all at once, which is contradictory to this idea that most people who are very prolific in art have to spend a lot of time alone. I guess maybe you did that when you were young?

HUO: Yeah, definitely. I have this Instagram where I post these handwritten notes every day. The artist Amani Howard, a young artist from Chicago, wrote, “Don’t be afraid to enjoy your solitude. It’s how you learn to be with others.” I think that during that time when I was really alone in my room in Switzerland for a year and I couldn’t do much, I was learning to be with others. Soon after that, I started to be obsessed by books and then by postcards, and art postcards when I was like eleven or twelve.

RM: You put the postcards on your bedroom walls, right?

HUO: Yeah, on my walls and in little boxes, building museums curated in my bedroom, in my little children’s room. I curated little exhibitions, and then when I was 16, 17, I started to meet artists.

RM: Do you consider yourself a prodigy?

HUO: No, no I don’t think so. I think that I found, quite early in my life, a vocation. It’s really been work. I went to the studio of Fischli and Weiss when I was 16, or 17, because I felt an urgency to visit artists, and they were making this film in the 80s which they finished soon after called The Way Things Go. It’s the famous chain reaction. The most beautiful equilibrium is the one that is just about to collapse. And so they did these photos of equilibriums and then they let them collapse and that triggered a chain reaction, which in the film seems seamless. Obviously, it was a montage.

RM: Well, that sounds kind of like the story of your life.

HUO: The book is about that. The book is a bit like that film. I would say no, I don’t think it has anything to do with prodigy. It has to do with a lot of work, but also letting things evolve. There wasn’t a master plan, but I had an enormous – and I still have every single day – necessity to know. I always look for knowledge. Then through that came the research, came the studio visits and, because I was so young, the artists gave me tasks…

RM: They gave you homework?

HUO: It’s interesting. Is it homework? It was actually like roadwork because I was traveling to meet artists by night train. Then Rosemarie Trockel said I should ask artists who their forgotten pioneers are, to look into the past, not only to younger artists. She said that there were so many female artists – I mean, Louise Bourgeois was famous then, in the 80s – but there were so many female artists who were not recognized. She said I should go from city to city and ask the artists of my generation who their pioneers were.

Then you visit them, and you have that exchange, make books and exhibitions. That was the “roadwork” she gave me. I couldn’t have done it from home. Then Alighiero Boetti said that I should ask all the artists about their unrealized projects. So I went by night train from city to city and did that. You’re right, it’s some form of homework, but it was maybe more like roadwork.

RM: Yeah, roadwork, that’s a better word for it, it’s funny. Do you think that you experience the same capacity for awe as you did when you were younger and seeing these things for the first time?

HUO: The same capacity for awe…There’s this conversation between Sergei Diaghilev and Jean Cocteau- Diaghilev was also very important for me because Diaghilev was the founder of the Ballets Russes, and he was a curator of paintings who then brought all the art forms together, people like Goncharova, Picasso, Stravinsky, and of course, Coco Chanel! From fashion to dance to visual arts, all through the Ballets Russes.

For me, as a teenager, that was really important. So there’s this famous exchange between Cocteau and Diaghilev, and Cocteau writes to him, “Étonne-moi!” (Surprise me!) I think that the idea of awe, but also of surprise is part of the marvel. I’m working on this project with the Louvre now, which is why I had to be there this morning. With the Louvre, basically, we are remaking this book by Pierre Schneider. In the 60s Pierre Schneider made a book of dialogues where he visited well known artists of that time, mostly based in Paris, some visiting Paris. He visited the Louvre with them to look at their favorite works.

I always believe that the future is invented with fragments from the past. It’s really important that we can look into the past and see how artists connect to it. Not static memory, but dynamic memory. So, Pierre Schneider went to the Louvre with artists like Miro, Barnett Newman, Maria Da Silva, Giacometti, and they showed him their favorite works, what they were inspired by. It’s hugely fascinating. This book is literally falling apart because I’ve read it so many times. I always went to the Louvre with it.

So now that a friend of mine is at the Louvre and bringing in many contemporary projects as a curator, he had this great idea together with the director, Laurence des Cars, to actually make this happen! Had you asked me three years ago, I would have told you my unrealized project is to one day do this Pierre Schneider project. And now the Louvre decided that they can do it, which is so great. So this morning we were with Simone Fattal, yesterday afternoon we were with Sheila Hicks. This afternoon we’re going to be with Daniel Guran and Anselm Kiefer, but also younger artists like Julien Creuzet who is doing the next French Pavilion at the Venice Biennale…And they’re all so fascinating, everything they show me. I’m in awe looking at all of these amazing artworks. It never fades. It’s infinite.

RM: You’re like devoutly religious, but to art.

HUO: For me, it’s hope. As Gerhard Richter says, art is the highest form of hope. For me, art is hope. The book is also about that in a way.

RM: Are you actually religious?

HUO: No. I would say, in that sense, that art is where I get my hope from. No, I’m not religious, but I have always been interested in what’s sacred.

RM: Do you believe in life after death?

HUO: Yeah, I think art has so much to do with that. I actually spoke about it with Simone Fattal this morning at the Louvre. You know, art is also about long duration. It’s interesting, if you look at previous millennia or centuries, I mean some of these objects are not even meant to last, but they do last. And others were meant to last, but it’s really fascinating that one day what we will remember from our time is art. Art will obviously outlast us. That goes back to your first question also. I think my work is successful if I’m useful for art. I want to be useful and help produce realities for art and artists. That’s the measure, in a way, of my success.

RM: At this point in your life, what are you most proud of? Personal or work-related. But I guess they aren’t really separate for you, are they?

HUO: Yeah. It’s a very blurred line between art and life.

RM: Sounds a little like you’re a workaholic, but maybe it’s more just like if you do what you love, you never work a day in your life?

HUO: It’s just like an infinite conversation. In this book – I’m going to show you this book by Pierre Schneider – you see, that’s the old book here, Louvre Dialogues by Pierre Schneider with all these artists. There is his interview there with Giacometti who says that all of our activity is really unconscious, except for dialogue.

The only thing of interest is a dialogue with somebody about something. In that sense, dialogue preserves us from finalities, from the final, from solitude, from endless heartache, and from sleep. It’s a readiness to take part in exchange. For Giacometti, the redeeming virtue of human beings is that we are capable of dialogue. That’s why Giacometti didn’t like sleep, because you’re always alone in sleep, and Giacometti liked places where people talk.

It’s interesting for me, this idea of dialogue. So, I don’t think that there’s anything I’m really proud of because it’s always about the next thing. It’s always about the next project for me. At the moment, my whole focus is on these Louvre conversations, and on the next pavilion that we are building at the Serpentine with this young Lebanese architect, Lina Ghotmeh, who is based in Paris. That’s the focus for me. It’s a process, it’s very dynamic, I’m not looking back and feeling proud. But there is something which I’m really, you know, happy about. I’m really happy that I recorded all these conversations I’ve had. I filmed some, I recorded lots of audio, and today I have about 4,000 hours recorded of all my conversations with artists.

That’s really the backbone of my entire work because it leads to writing. A lot of my exhibitions grow out of these dialogues. I’m eternally grateful – again to an artist – for this amazing thing Jonas Mekas, the filmmaker, gave me. I met him when I was maybe 22 or something, and I had already started doing all these conversations with artists since the 1970s, but I had not recorded them. I just took notes.

He basically said, “You’re going to regret this one day.” He was always there, in his cafe in Paris, we were sitting outside, and he was always filming with his super eight. And he said, “You’re going to regret this! And now we have these little cameras!” The digital cameras at that time were still bigger than these phones.

RM: Oh no. Should I be filming this?

HUO: No, the audio is also good. A lot of my archive is audio, and then it depends on the situation. Sometimes I film, sometimes I record audio, but he (Mekas) just said record. For me to have that archive today is incredible because we do lots of exhibitions with it. It’s in Arles at LUMA. I don’t know if you’ve been to LUMA in Arles? Maja Hoffman had this visionary project in which I was involved with from the beginning. Her vision was always to build this art center, LUMA, with a really amazing park.

I have worked with Maja as a senior artistic advisor since the beginning of this project in the build-up. Now there’s this set of spaces by Annabelle Seldorf, the Frank Gehry tower, it’s also a campus, there’s the Atelier Luma, and there is also my archive. Now every year we do an exhibition out of my archive. We use videos and audio and we make a presentation of all the conversations I had with someone. We did Édouard Glissant two years ago. Last year we did Etel Adnan, that’s still ongoing until the end of May. Then this summer, we will do Agnes Varda. You should come and see that. That’s going to be in early July. She was a very close friend, it will be of all my conversations with her.

So, it’s not that I’m proud of it, because it’s still only a beginning, and like I said, there’s so much more to do because it’s all about the future. But I am very happy to have this archive- it’s like the source.

RM: My grandmother just turned 80, I called her and asked if she felt 80 and she said “NO!” Haha. Do you think that, for you, probably thanks to art and this infinite dialogue- Do you still feel very young, even as time passes?

HUO: Yeah, I think it’s a mindset. For me, I always feel I have just begun, I’m learning. I feel like an eternal student. I do feel young. Yes. I always try to learn from these very old artists I’m meeting. I met a lot of centenarians, people in their 90s, like people who are 99, 100. I have a whole series of interviews with centenarians, people who have lived for a whole century.

I worked once with the artist Luchita Hurtado and that really was such an amazing experience because she had never exhibited in a museum before. We did her first museum show when she was 98 or 97. At the opening, we sat there and everybody was wondering, when is Luchita going to go home? She didn’t go home. She sat and drank coffee. Then at eleven, she says “I’m now retiring, I’m going to go home.” We arranged a car for her and she took the dinner menu and put it into her little bag. Then I said, like, “I’m so sorry we didn’t pay attention and we didn’t design this menu very well! If I had known that you would keep it, we would have done a better job designing it.” She said “No, it’s not about that. I just want to remember. This is a special evening for me, and when I’m going to be old I want to remember.” You understand? She was 98

RM: “When I’m going to be old!”

HUO: She felt young at 98. That’s what it’s all about. It’s a mindset.

We have been sitting parked in the cab to avoid the rain, but are beginning to block traffic.

RM: I have one last question. Do we have time? Probably not?

HUO: Well, we can maybe stand here-

Obrist gestures to a doorway with a little overhead covering us from the rain.

HUO: It’s an interview on the move!

RM: Haha. It’s perfect. Thank you again for making yourself available to do this.

HUO: I really like the questions.

I think maybe he is being kind.

RM: Well, I wanted to ask you, you know, there’s a lot of philosophical thought around the relationship between being, thinking, and walking, you know, from Hegel to Nietzsche to Heidegger. Nietzsche said the only interesting thoughts one has is while walking… I’m thinking maybe at The Obrist Institute, the “Obristian” school of thought would be that instead of through walking, thinking and being happens more through asking and answering each other?

HUO: I think the institute could be a rendezvous of question marks.

RM: A rendezvous of question marks! That’s great.

HUO: That could be a working title. I come very much from this idea of the walk, and of Robert Walser. Of course Nietzsche went on walks in Sils Maria where he had the epiphany of the “Eternal Return.” I did a show of Gerhard Richter many years ago about Nietzsche, in Nietzsche’s house…

But Robert Walser was my key childhood influence. He is this writer from Switzerland, from the mid 20th century, who went on endless walks. But for the moment he has stopped writing, because he says his new writing is walking. There is a book by Carl Seelig called Walks With Robert Walser that has now been translated into English. I built a museum in the 90s, an homage to Robert Walser. It’s a museum about going on a walk. Your question is totally connected to my long interest in that.

I have also done seminars- I was teaching once at this institute with Philippe Parreno, and he suggested that we do this seminar with 20 or 30 students as a walk up a mountain.

RM: Haha! When you’re in Paris, and it’s not raining, do you usually walk?

HUO: Yes, always. I would have walked here! Yes, of course.

RM: Thank you so much.

—

Obrist hurries across the street into a gallery. I wander into an art bookstore nearby. Just browsing, I notice at least five or six books that Obrist has either written or contributed to. Throughout our conversation, I found myself of course mesmerized by his immense knowledge, but more than that, by his excitement- Obrist’s eyes light up and widen with every other sentence that spills out of him.

If this is everything he can say in 25 minutes, can you imagine all that the book includes?

“Une Vie In Progress” is available to purchase at the Pharmacie des Âmes, 25 Rue Vaneau. Merci, Hans.