“Painting doesn’t exist for me,” Louise Bourgeois once said, as quoted by one gallerist of the historic Galerie Lelong & Co. during her introduction to Bourgeois’s paintings, drawn images, and engravings from the I do, I undo, I redo exhibition. Despite this ostensible rejection of painting, however, much of Bourgeois’s work—and every piece in this show—discloses an affinity for the drawn image.

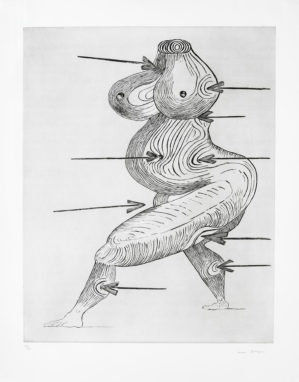

Her most notable work currently on display is perhaps the Sainte Sébastienne (1992). In Bourgeois’s rendition of the early Christian saint, which has been the subject of many paintings throughout the history of art, the androgynous Sebastian is rendered headless and female (hence, Sébastienne) with a body resembling a tree trunk. As with other depictions of the martyr, Bourgeois’s own includes an arrangement of arrows piercing Sébastienne’s body, yet the characteristic violence of this assault feels muted in hers, not only due to the somewhat abstract, geometric portrayal of the body, but also because the headless figure lacks a face through which to communicate any expression of hurt whatsoever.

This quality of subdued agony is heightened by the positioning of the arrows, none of which fully pierce Sébastienne’s body, and some of which even leave the body entirely untouched, merely gesturing towards it, resembling an anatomical chart of sorts rather than an aggressive attack. This is not to say that Bourgeois’s Sébastienne is absolutely lacking in violent tenor—in her own words, “Sainte Sébastienne is a self portrait. It’s a state of being under attack, of being anxious and afraid.” Strangely, then, the conveyance of any emotion related to the states she describes presents itself as shadowed, rather than immediately and necessarily apparent.

One might understand this understated representation of pain and suffering as symptomatic of Bourgeois’s own struggle to negotiate emotional and physical hardship—a recurring theme in her oeuvre—or, more grandiosely, as emblematic of a woman’s burden to bear her suffering silently. One might also choose to consider the material form of Sébastienne to approach an understanding of these themes: how does the material of the work contribute to our understanding of it? Why print on paper? I find these questions to be intriguing especially when considering Sébastienne as a self-portrait: why would an artist whose work typically takes the shape of large-scale sculptures and installations in bronze, marble, and plaster, portrait herself via drypoint printing on paper?

One effect of drypoint printing is of course the replicability it enables: Bourgeois printed numerous, dissimilar renditions of Sébastienne, each exploring the themes of (gender) identity and pain. The serialised nature of Sébastienne encourages an understanding of this “self-portrait” as a continuous attempt to portrait the self, a consistent endeavour to re-present herself, to make present her self-understanding, only to realise perhaps that her identity is always slipping away, always demanding re-presentation once more, ad infinitum. This reading of Sébastienne in terms of a struggle to portrait the self, rather than simply as a self-portrait per se, becomes more convincing when one acknowledges the obvious: the printing of Sébastienne eventually concluded with a beheaded Sébastienne, a portrait with no face.

Removing what is traditionally the focus of portraiture, the beheading of Sébastienne frustrates our experience of this final version as a self-portrait, and perhaps indicates Bourgeois’s own frustrations to carve out an identity for herself in a world in which she feels “under attack.” Moreover, too, unlike historic representations of Saint Sebastian, in which his body is tied to a tree, Bourgeois’s feminized Sainte Sébastienne becomes the tree through her trunk-like body. Whereas Saint Sebastian maintains his head and beautiful body in historic depictions, Bourgeois’s Sébastienne is almost entirely without an identity, loosing both her head and becoming something wholly other in body, an object in the world (a tree trunk) rather than a subject of it. To add a further layer of signification, the paper on which Bourgeois printed literally mirrors, serendipitously, this final relationship to the tree-trunk and, as opposed to sturdy bronze or marble, the fragility of paper appropriately echoes the vulnerability expressed in Sébastienne, as well.

But before I even visited the Bourgeois exhibition, I was elsewhere in the Galerie Lelong & Co., in a gallery room accessible by an entirely different entrance to the building, to view Richard Serra’s Casablanca. As is the case with Bourgeois, Serra is know for his large-scale sculptures, mainly in steel, and his installations. His Casablanca series, however, is six works of oilstick, ink, and silica on paper.

In this series, black masses with differing curvatures are printed on paper, produced in collaboration with master printer Xavier Fumat at the Gemini G.E.L. workshop in Los Angeles. The arched shapes immediately reminded me of his Torqued Ellipses series on long-term view at the Dia:Beacon in New York. While plainly different in form and scale, Ellipses and Casablanca similarly rouse viewers’s awareness of space and movement. While the former more blatantly entreats one to be aware of the physical, insofar as one must manoeuvre around massive steel sculptures, the latter allows viewers to remain in place, standing surrounded by six prints all in the same room, as the black masses themselves seemingly shape-shift, manoeuvring around the viewer. The experience can be rather disorienting, if you allow it to be.

I brought my face near one of the prints and it became clear that what seemed from a greater distance to be a distinct boundary between black mass and white paper was, in fact, a boundary continuously being trespassed. In Casablanca, the authority of the black spills out onto the fragility of the white, primarily a result of the textured oilstick (see ‘Image 1’ in gallery). What from afar appeared to be balanced separation of colour became on closer inspection a relationship in the balance, not only of colour but also between the smoothness of the paper and the sharp texture of the paint. The black and white prints increasingly appeared to me as prints of black in white, of black violating white, of a negotiation of space represented by colour and shape. This tension is reinforced by the paper canvas on which this theatre played out: the fragility of paper highlights the forceful presence of the black mass.

This theme of uncertainty that I began to notice in Serra’s exhibition (the uncertainty of boundaries and space) and saw traces of later in Bourgeois’s work (the uncertainty of identity) came to mind clearly as I exited Galerie Lelong & Co. once more onto the streets of the 8th arrondissement—thankfully the sun shone in Paris that day—to walk a few blocks south towards Duo sur scène, the exhibition of Jan Voss. While all three gallery rooms belong to Galerie Lelong & Co, each is spaced apart with individual entrances. Walking in and out of these spaces, I embodied a solitary game of tug-of-war with myself as the rope and the different spaces as competitors struggling to pull me about. The impact that Serra and Bourgeois’s work had on me was such that it encouraged an understanding of my physical experience at Galerie Lelong & Co. as a curious state of uncertainty.

As I arrived at the final exhibition currently on view at the gallery, I noticed immediately some of the material of Voss’s work: paper. The gallerist alerted me that Voss had written a short text about the exposition in which he mentions, among other things, the materiel of paper: “Monsieur Papier…prefers the same intense accoutrement of colours, sometimes exclusive, but with multiple tonal interferences. In his case, the contours are less clear-cut, the boundaries between different territories less controlled, with intrusions allowed.” At Voss’s exhibition the motif of paper present silently both in Serra and Bourgeois’s work emerges undeniably in the spotlight here in personified form. Equally, the themes of uncertainty, of boundaries, of tensions, are present in Voss’s work, too. There is much else to say to say about Voss’s vibrant exhibition, and his career, which spans decades, but all this one should explore further oneself at Galerie Lelong & Co.

These three exhibitions are on view through April 30th at Galerie Lelong & Co., Paris: Louise Bourgeois’s I do, I undo, I redo and Richard Serra’s Casablanca at 13 rue de Téhéran, and Jan Voss’s Duo sur scène at 38 avenue Matignon.