Dear Shaded Viewers and Diane,

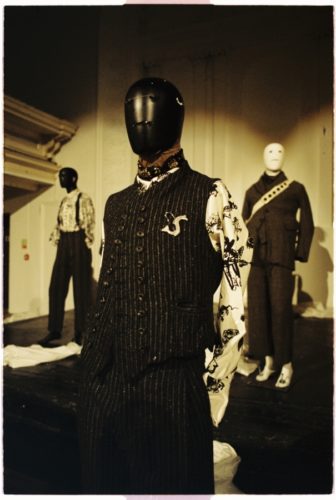

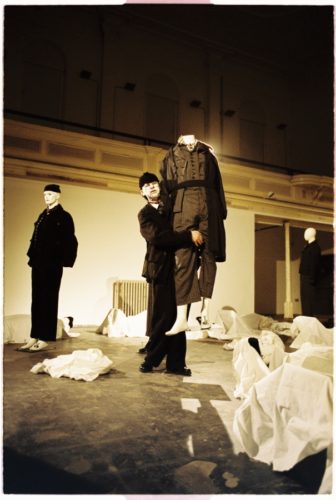

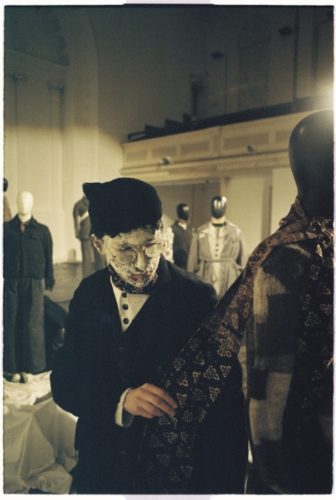

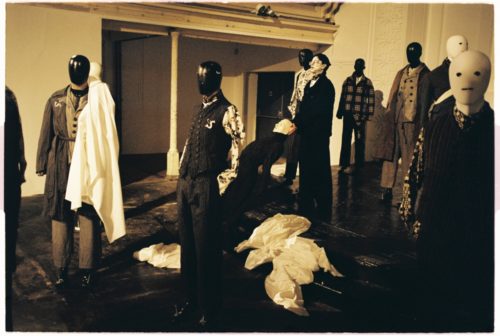

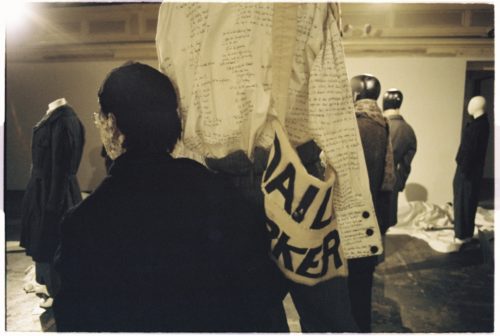

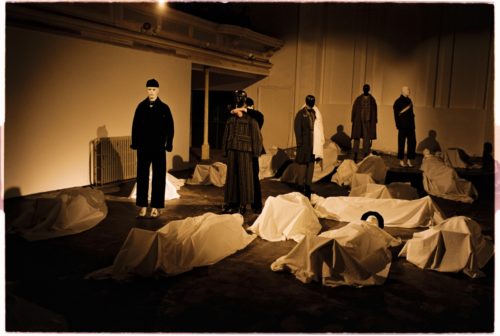

Its testament to the reputation he’s built for his brand over the past handful of seasons, that though not on schedule, still the editors of everything that counts picked themselves up from their seats late after the last show on Sunday, to make their way to the Zabludowicz Collection in Kentish Town, North of London, where John Alexander Skelton’s latest collection was presented as a one-man play. It was a moonless night. As moonless, as the omniscient narrator, his face caked with white paint, proclaimed the night in Llareggub to be. It was our cue to understand that the auditorium of the former Methodist chapel where we stood, an art gallery by day, was to turn for the night into the fishing village that Under Milk Wood, the 1954 radio drama by Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, is all about: where a whole small town of characters just go about their day. It begins when they’re all asleep, and so all dressed-up in Skelton’s outfits a number of mannequins lay on the floor, covered in white sheets. As he recited Thomas’ words, the white-faced narrator, almost blending in among them, unveiled and woke and stood and moved them around to play their parts. If not the choice of mannequins rather than people, the decision to have these mannequins in particular wear Skelton’s exquisite pieces could have seem misguided at first: cautiously expressionless, a few were those most common high-street mannequins whose slender proportions we’re all well-familiar with. But this too, of course, was for a reason. What Skelton loves about Under Milk Wood, so the show notes he wrote say, is the text’s ‘surrealistic view of the banal’, the, in Thomas’ words, ‘salty individuality” of people engaged in everyday activities. Fashion’s brief love affair with the mundane – remember normcore? – is something we’ve left behind well before this New Year’s Eve. Yet for a designer who’s making a name for himself by way of his hand-made, one-off pieces, this unusual theme became eventually the best of challenges. He started with the most banal of colours, grey, and looked up the sheep breads in Britain whose coat is naturally grey, to then mix in a single garment as many as eleven shades of grey wool, woven in Scotland by local artisans. The individuality of common people was given by cloths that were purposefully washed, felted and tumbled to look worn-in, dishevelled as poets themselves. History always informs this designer’s method – indeed, this was not a fall 2020 but an VIII collection, for Skelton’s work follows its own timeline – and in this instance it worked to further stress the sense of familiarity, of mundanity, that he was striving for here. Although for several decades now, we can deem these clothes familiar only if we take into account archive images and period costumes. In this uncertain future that we live in, Skelton appears to wish and resurrect a simpler – perhaps banal – past. If the crowd that filled the space to congratulate him and examine and touch his clothes – something established designers still shy away from – is anything to go by, it’s a wish that many of us will share.

Later,

Silvia