Dear Shaded Viewers,

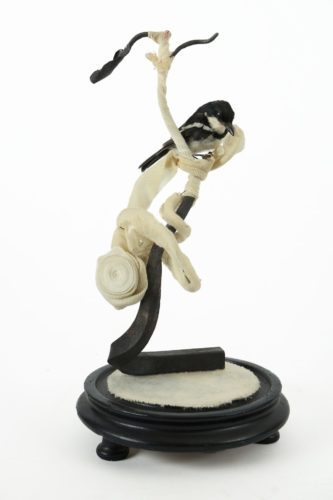

Once upon a now and yet-to-be, in the wild mosaic of Dutch art, two visionaries named Afke Golsteijn and Floris Bakker became the keepers of wonder. Born in Amsterdam’s haze in 1975, their meeting was no idle chance but a fateful intertwining of roots at the Free School, and later the Gerrit Rietveld Academie. From the very start, their hands reached for the unlikely—the lifeless, the lost, creatures passed over by life itself. Their art, like a spell, transformed the fallen—birds and beasts—into objects of fragile beauty and haunting memory, blurring the word between fantasy and reality, much like the fables that first inspired them.

Yet their story, though stitched with the feathers of taxidermy and the shimmer of pearls, finds its deepest song in the realm of green. The land itself, the breathing stretch of plant and soil, became the theater for their most enchanted works. In their atelier at Het Domijn in Weesp, a living garden swells and shrinks with the seasons. Here, they craft not only from what is lost but also from what still grows—veins, branches, roots, and rituals—that connect all living things.

Their plant-based art is a fairy tale sung by the land. Consider “Lungs” (2022–2025): a living network, braided from hemp, forming the tracery of veins, a quiet echo of both plant and animal anatomy. Whispering with green breath, “Lungs” spent three seasons under the sky, soaking in rain and sun, before moving indoors where its pulse continues, independent and alive. Its cousins, too—“Sacred Heart,” shaped so a plant’s roots became a human head, its woven body a trinity of stem, nerve, and leaf—find sanctuary in sacred spaces, revered for their quiet sanctity and the suggestion that perhaps all hearts, green or otherwise, share one longing.

Land art, for Golsteijn and Bakker, is more than spectacle; it is healing action upon the world. Where once there was a polluted dump, they coaxed forth a lush new wilderness, transforming waste into wildness. Their hands became magicians’ wands—turning scars in the earth into living shrines, showing that nature’s recovery is also a kind of art.

Their installations grow in or out—blossoming in the garden, then finding new meaning indoors. The intertwining of roots and reclaimed land reflects their guiding belief that every artwork is an ecosystem, an intricate web where one life supports another. They conjure up the fables of old—Adonis gardens from Greek myth, where lettuce and barley grow swift and wilt just as quickly, celebrating beauty and loss in equal measure. Their work, like the gardens of Aphrodite, speaks of cycles: quick green, quick gold, and the wisdom of letting go.

And so the world takes notice. Their art is seeded across the globe—CODA Apeldoorn, the National Museum of Oslo, Auckland Museum—each a plot in their far-reaching forest. Their international exhibitions are not only showcases but crossroads, where nature’s resilience blooms on the eyes of those who wander through.

Golsteijn and Bakker’s fairy tale, then, is woven of thistledown, moss, and memory—a tale where every sculpture sways with the wind, every plant is a silent prophet, and every transformed landscape becomes a living fable. In their world, the magic is not in what perishes, but in what persists: the hopeful, ever-tangled green thread running under everything, urging us all to begin again.

Later,

Diane