Dear Shaded Viewers,

The upcoming POLARAKI exhibition at the Musée Guimet in Paris is a revelation—a labyrinth of vision and obsession where Nobuyoshi Araki’s thousand Polaroids form an electric gridwork of love, loss, and erotic chaos. From October 1, 2025 to January 12, 2026, Araki’s aradise, a collection assembled and orchestrated by collector Stéphane André, takes over the museum’s walls—a transfer of private ritual to public curiosity. Here, the press release becomes haunted narrative.

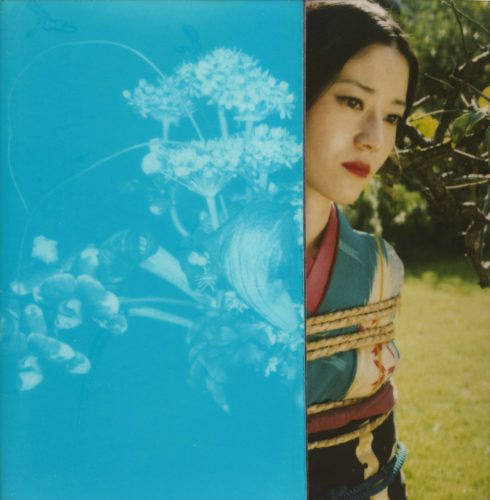

Araki’s ritual, begun in the 1990s and eventually devolved into daily necessity, is an act of capturing breath—using the Polaroid not as a mere snapshot, but as a meditative journal of mortality and longing. The instant photograph, for Araki, is not just about recording what passes by, but touching the soft core of what refuses to fade: intimacy, sex, the withering and the bloom of flowers and bodies. “Les polaroids [d’Araki] ne représentent pas seulement des fleurs, à foison. Ils sont des fleurs,” writes Stéphane André. The act is not documentary—it’s physical, a form of poetry that cannot return, a petal pressed forever.

POLARAKI, as staged, exposes nearly a thousand images—906 Polaroids encased in 391 frames, half arranged by Araki, half by André, in patterns echoing the Japanese artist’s own visual poetry. There is chaos—gridwork bearing the residue of eroticism, personal mythmaking, and a willingness to linger on the edge of obscenity. Some frames are left vacant: a quiet nod to the models whose bodies resist display. Here is curatorial dignity—a dance between vulnerability and discretion. The installation is more than a wall of images; it’s a living cabinet, a private mythology made public.

The exhibition refuses easy mythologies. Araki’s notorious Kinbaku, his fascination with binding bodies as with tying off florals, runs parallel to Japanese erotic woodblock prints, the shunga, and the martial arts of rope—kinbaku, hojojutsu. Yet contemporary eyes reclaim agency, pausing at the border where artistic tradition once legitimated violence and objectification. The press release signals a shift: Guimet and its team refuse to allow history to overwrite dignity. Lingering questions resurface about representation, trauma, and the artist’s relationship to the female body.

The unseen heart of POLARAKI is transformation—André’s apartment, with its grid of Araki polaroids, now reborn inside Guimet, a reassembled intimacy set beneath vaulted ceilings and institutional lighting. The journey from domestic sanctuary to public spectacle is not simple: André’s hand remixed the grid, extending the artist’s game. This is curation as conversation, each frame a dialogue between collector and creator, longing and letting go.

POLARAKI is not static. Its calendar pulses with dialogue: historians, poets, and researchers convene to dissect the knotty intermingling of love, mortality, and erotic power. On October 4, curators Cécile Dazord and Édouard de Saint-Ours, joined by historian Elise Voyau and arts scholar Christian Musso, unpack the knotwork of womanhood in Araki’s lens. Later, novelist Natsuki Ikezawa casts new light on Japanese literary eroticism. Throughout, the museum’s architecture flexes to accommodate both the violence and beauty of Araki’s visual language.

Araki’s work is a recent pulse inside a museum whose archives stretch back to 1850, touching the history of Asian photography from early documentarians to modern provocateurs. Guimet holds more than 600,000 images; POLARAKI is its fever dream—a rare moment when a living artist’s obsession is allowed to flicker and burn inside a site built for commemoration.

POLARAKI is rupture, survival, and sensual honesty—a thousand blooms unfolding inside glass. Araki’s obsession, refracted through André’s curation, becomes the museum’s new heartbeat. Its aftertaste is both feral and dignified, seductive yet prone to breakdown. Through the haze of Polaroid gloss, the exhibition asks: What is left after intimacy is archived? And in the softness of blank frames, what remains when the model walks away? POLARAKI breathes, resists, lures. It is the museum’s most vulnerable offering—blossoming, wilting, refusing to disappear.

Later,

Diane