Marin Karmitz, renowned figure in French cinema and passionate art collector, has generously lent his extensive photography collection to the Centre Pompidou as part of their latest exhibition, Corps à Corps. The show is a captivating, comprehensive analysis of the interplay between the frame, human form, and the role of the author that pays homage to the profound storytelling capacity of photography with a point of view that only someone with Karmitz’s deep cultural references and cinematic background could contribute. The collection includes more than 500 works of over 120 renowned photographers- it is the largest collection of photography that I have seen in a contemporary art museum- a curatorial and pedagogical triumph. A friend accompanies me to the vernissage and notes, “This is the sort of thing you would see on a much smaller scale at an art foundation or at Le Bal. You know, photography is the bastard child of art, and documentary photography- the bastard child of photography.. C’est incroyablement beau.”

At cocktail hour on the rooftop terrasse there seem to be perhaps more prominent figures of French cinema in attendance than those of art- in the corner Lea Seydoux and Irène Jacob are having a laugh and drinking champagne. It’s an affair of cinematic aristocracy, a love letter to nouvelle vague, the human condition, and deconstructionism- to the romance of realism, ambiguity, and the limitlessly imaginative liminal spaces left in work marked by these characteristics that invite the viewer to participate as a narrator. Consequently, the exchange between the audience, work, and author holds an exponential capacity for intimacy, and we are reminded of why the films of nouvelle vague are so highly regarded and admired. The work becomes accessible, moving, and intimate- beckoning empathy and participation.

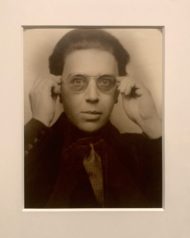

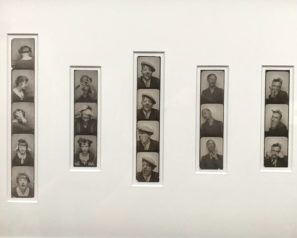

The collection is presented in chapters which examine how the body occupies a photo and defines its identity, and how the relationship and roles between the photographer, subject, and audience, shift and transfer through different approaches. Roland Barthes’ theory of “la mort de l’auteur” (the death of the author) maps out the intellectual course of the exhibition beginning with images of faces and early portraiture that transition to self-portraits and then to the invention of the photomaton which eliminates the photographer and allows the subject to capture and curate their own identity and artistic agency. This quality made the machine quite popular amongst the surrealists. Take for example these photomaton portraits of Marie-Berthe Aurenche, Jacques Prévert, Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, and Andre Breton.

Another from this collection, S’He (Self Portrait with Wig) by Ulay-

–

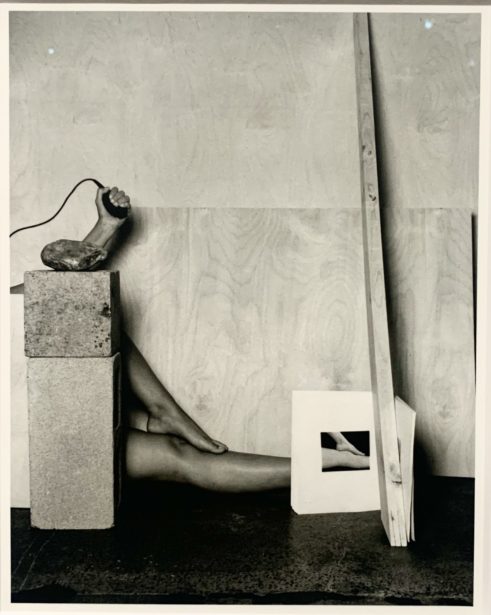

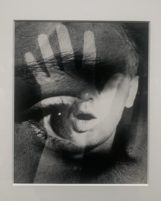

In another room, in images of fragmented body parts, anonymity lends to eroticism. The viewer becomes voyeur, and the subject and desire is sublimed. As an author pens a work or character, a photographer captures a subject, but it is the position of the viewer that interprets the story and their subjectivity which fills in the contextual blanks and gives it depth. In a 2017 documentary, Marin Karmitz stands beside the photo series Les Mains Pragues by Christian Boltanski and explains, “When people visit me, I tend to sit in front of this piece. And very often when I’m bored [looking at this piece] lets me escape and tell myself stories. Limitless stories, because I’ve never found out whose hands these are, and what bodies and faces are hiding behind them. There is an incredible mystery that emanates from these hands. I enjoy less and less art without mystery.”

More images of fragmented parts from the exhibition in photographs by Nancy Wilson-Pajic, Eugene Smith, and Tarrah Krajnak-

–

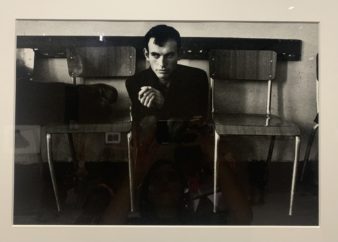

Further on, portraiture in self-contained, “heterotopic” spaces- a term coined by Michel Foucault- explores the liberation of untold or hidden stories. Photos of subjects self-contained in themselves, in thought, ring melancholic and isolate the subject, while investigating spatial perspective to relativity. Chris Marker’s 1999 photograph Sun Eclipse, Paris identifies an exterior context, we observe the observers from the midpoint of their own line of sight to enter a new space that the camera creates which elicits a large, intangible, impending sensation.

Another effective demonstration of photography within heterotropic spaces are these images taken by Raymond Depardon of psychiatric hospital patients in San Clemente, Italy-

–

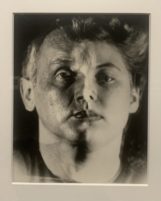

The final chapter is titled Ghosts– a collection of images that utilize manipulating the technology (light, montage, shutter) which usually serves to clarify the subject in favor of erasing the individuality in an effort to “reveal an experience of transition [and to] underscore a passage.” Here we arrive, further referencing Foucault, to the “death” of the subject, and the exploration and perversion of technique to explore larger narratives. Some images from this collection include these works by Val Telberg and Vivian Maier-

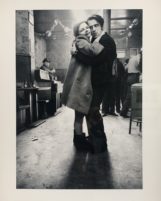

Christian Boltanski’s La Dernière Danse is another haunting example of this. In this diptych Boltanski has reappropriated images of passengers on a ship carrying Romanian Jews fleeing to Istanbul in 1941-1942 that were mistakenly torpedoed by a Soviet submarine, leaving a lone survivor. The enlarged blurred images with warm overhead light illuminate the larger narrative- a long journey and a mass tragedy. Many more subjects than the two in these images are represented and felt. But upon first glance, they do seem to be just two lovers dancing-

–

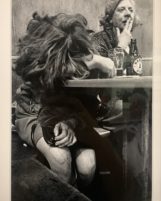

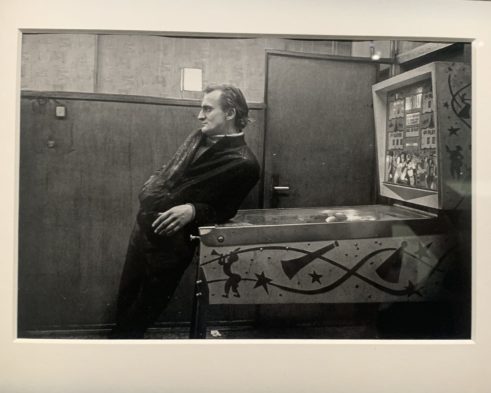

And finally, some personal favorites from the exhibition taken by Swedish photographer Anders Peterson-

Many thanks to the Centre Pompidou for inviting ASVOF to discover this extraordinary exhibition. A must see! For more information on Corps à Corps and to book a visit please head to https://www.centrepompidou.fr/fr/programme/agenda/evenement/CGOU5n9 .