Dear Diane, dear Shaded Viewers,

I had a long professional relationship with Ron Galella, which started in the early 2000s when I interviewed him for DUTCH magazine. Over the years, I collaborated with him on his essays for his many photo books and contributed my own essay to Pop, Rock & Dance. Ron and I had a working-class Italian American bond and I have fond memories of dining with him and his wife Betty at various Italian restaurants in NJ and NYC. Ron recently passed away at the age of 91 and I found this profile I wrote on him in 2003 for the Holt Renfrew magalogue, when I visited his home and archives in New Jersey.

Ron Galella

By Glenn Belverio

Perusing the oeuvre of 72-year old photographer Ron Galella, one could get the impression that his work is all about hands. And not just the outstretched, banishing palm which is the international sign for “Don’t take my picture!”, but hands that tell other stories as well: Peter Falk’s heavily bandaged hand, Barbara Streisand’s jumbo diamond ring bearing hand, Diana Vreeland’s chicly brandished claws gleaming with scarlet talons. Upon closer inspection of the photographs, it becomes evident that the hands are merely the proverbial tip of the iceberg, and that the man behind the camera rightly deserves the tag “Dean of the American Paparazzi.”

“I defined what ‘paparazzi’ is,” boasts Galella, not unjustly. “Off-guard. Spontaneous. Unrehearsed. The only game.” ‘Game’ is an apropos description when one examines Galella’s photos of a certain woman who often seems to be eluding pursuit; running through Central Park like a hunted gazelle or shielding her face with a bouquet of flowers or the collar of a turtleneck sweater as she ducks into her apartment building. “Jackie Kennedy Onassis, the most desirable woman in the world wanted to be chased by me, Ron Galella, the paparazzo. I knew even then that there could be no stopping, no turning back,” Galella wrote rather hyperbolically in his obsessive 1974 book Jacqueline.

Jackie was Galella’s most famous subject, and he hounded her relentlessly, whether she was emerging from her Fifth Avenue apartment, strolling through the yard of her Peapack, New Jersey bungalow, or relaxing in Skorpios with Aristotle Onassis. “My interest in Jackie was a love of adventure, a love of hunting someone down and capturing the picture,” explains Galella. “She didn’t make it easy, so it was a great challenge and I like that.”

Despite Jackie’s resistance – she took him to court and obtained an injunction that prevented him from photographing her for four years – many people today agree that Galella’s shots of the famous First Lady are what cement her image as an eternal icon. “They say I kept her alive,” muses Galella. The most well-known photo was taken on October 3, 1971 – ‘Windblown Jackie’, Galella’s Mona Lisa. “It has all the characteristics of paparazzi photojournalism: spontaneity, the wind blowing in her hair, natural lighting, no makeup,” says Galella. “That’s what I look for – the real person rather than the contrived shot with lots of makeup and phony smiles.”

“Jackie Kennedy Onassis, the most desirable woman in the world wanted to be chased by me, Ron Galella, the paparazzo.”

Galella was raised in a working-class Italian American family in the Bronx and enlisted in the Air Force at age twenty. He began his career as a photographer by shooting for the base newspaper while stationed in Orlando, Florida during the Korean War. After he was discharged, he used his GI bill to attend the Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles and graduated in 1958 with a degree in photojournalism. He moved back to New York and worked from his father’s house in the north Bronx.

“There was a recession and I couldn’t afford my own studio in New York so I started shooting celebrities on location,” he explains. And where was the best place to shoot celebrities in their natural habitat? Hollywood, of course. Once Galella became more established in the late ‘60s he began traveling back and forth between New York and California, and it was in LA that he shot some of his most engaging images. His strongest period was the 1970s when his reality-based photography style was in perfect sync with that decade’s gritty approach to filmmaking, a time when Hollywood had largely discarded the sugar-coated schmaltz of 50s and 60s artifice.

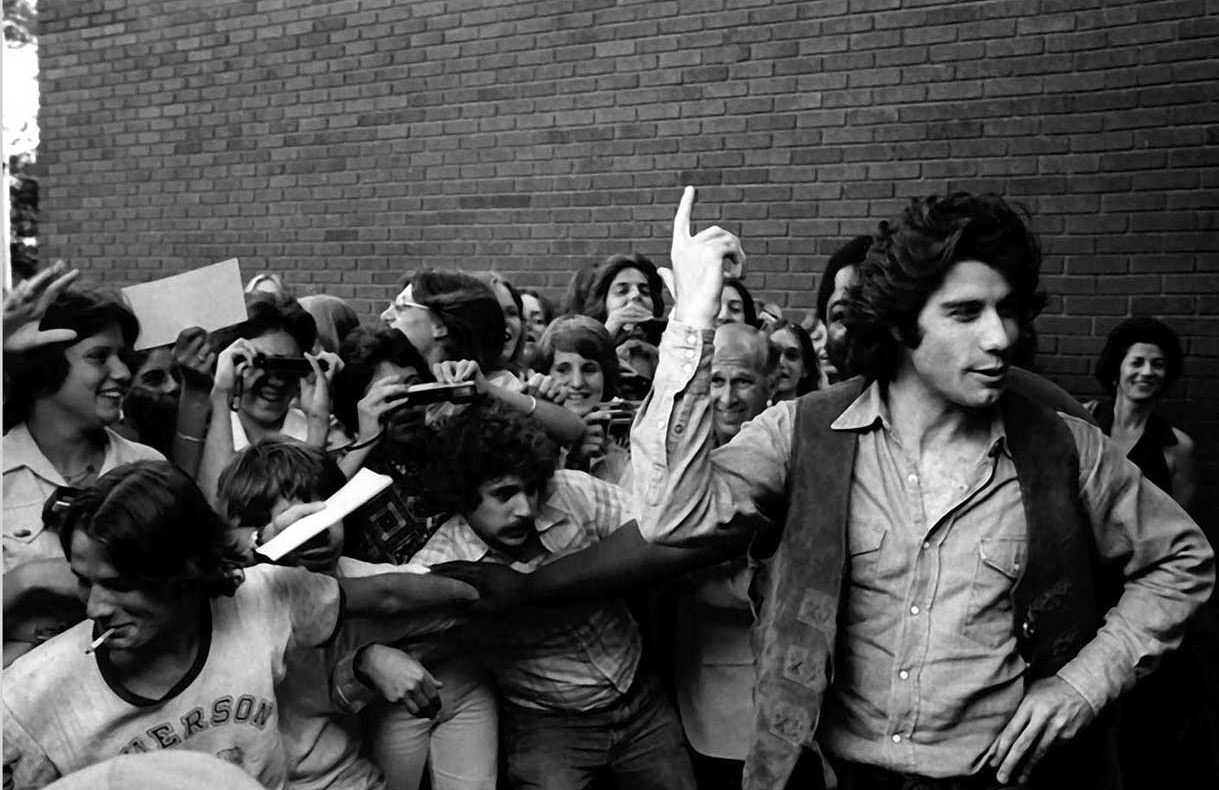

Among the panoply of images from 1965-1989 in Greybull Press’s beautifully printed The Photographs of Ron Galella, which is out this fall in paperback, this period in Hollywood is chronicled in all its fascinating, narcissistic splendor. Here is a startled Bette Midler looking behind her shoulder at the Grammy Awards, her askew tiara making her look like a lost, overgrown trick-or-treater. Alfred Hitchcock at the premiere of his film Family Plot wearing a stony, zombie-like expression that recalls Tor Johnson’s performance in Plan 9 From Outer Space. A pre-Saturday Night Fever John Travolta already basking in fame, a crowd of fans restrained mere inches away and behaving as if Travolta’s then unadulterated charisma had driven them to fits of ecstasy. And a miniscule Herve Villechaize ducking under a velvet rope at the Golden Globe awards like a mischievous gremlin hell-bent on carrying out acts of sabotage on the glamorous proceedings.

Despite Galella’s cinema verité hand, there is a persistent dream-like quality that emerges throughout the book. There are moments when the images almost threaten to tumble into a vortex where reality and fantasy merge – like the spiraling narrative of the amnesiac actress in Mulholland Drive, David Lynch’s savagely surreal commentary on Tinseltown. Or as Madonna put it more succinctly in her recent single “Hollywood”: “I’ve lost my memory in Hollywood/I’ve had a million visions bad and good.” Of all the visions in Galella’s work, however, the most sobering seems to be the reminder of the ephemeral nature of fame and flesh.

To understand the genesis of the paparazzi, one must look back to a former film capital, that Hollywood-on-the-Tiber known as Rome. “While creating La Dolce Vita, Fellini assigned the name ‘Signor Paparazzo’ to a character in the film, a photographer who was always scurrying up and down Rome’s Via Veneto snapping candids of movie stars and other strolling celebrities,” Galella explains helpfully in his 1976 book Off-Guard. During those heady days in late-50s’ Rome, paparazzi such as Felice Quinto tracked glamorous quarry like Fellini actress Anita Ekberg, whose response was to turn a bow and sharp arrows at her hunters.

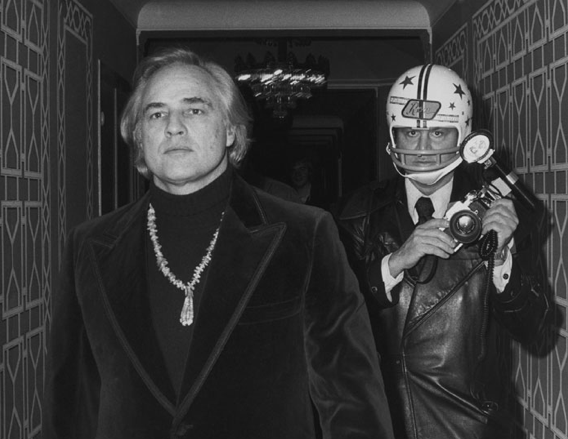

Galella, who is credited with establishing this distinctly Italian art of photography in America, has also had more than his share of celebrity slings and arrows. “Marlon Brando knocked five teeth out of my mouth in 1973 when I asked him to take his sunglasses off,” Galella recalls as if it were yesterday. “One of my teeth was embedded in his hand which became infected. He has scars to this day.” A subsequent photo of a football-helmet-clad Galella trailing Brando is an iconic image of the photographer’s legacy.

In St. Tropez, Brigitte Bardot’s beau tried to hose Galella down and ruin his camera when the photographer snuck shots of the blonde bombshell swimming. And in Mexico in 1971, on the set of Elizabeth Taylor’s flop film, Hammersmith is Out, Richard Burton ordered crew members to beat Galella up and destroy his film. To add insult to injury, Galella alleges that Burton had him banned from the Tony Awards for four consecutive years.

But these days Galella has gone from inciting celebrity ire and contempt to becoming a bit of a celebrity himself. His work is frequently displayed in galleries where stars gather to admire their own history. “One of the factors is that I shot them when they were younger and more beautiful and that’s what the last book captures,” Galella explains. “That brings back nostalgia for them.” Ironically, the American paparazzi craze that Galella inspired has become so huge that it has not only virtually excluded the man who pioneered it – he still has problems getting into events – but it has changed and cheapened the caliber of the craft’s output.

“There are too many press agents and many of them don’t know what they’re doing, and all the photographers are calling out to the stars, so everyone gets the same picture,” complains Galella. Another problem is the solipsistic attitude adopted by celebrities in a post-9/11 world – they fear becoming targets of terrorism and the result is truncated red carpets and excess security. “Yeah, Saddam Hussein was looking for the cast of Friends,” Galella’s wife and business manager of twenty-four years, Betty, sarcastically quipped recently.

His strongest period was the 1970s when his reality-based photography style was in perfect sync with that decade’s gritty approach to filmmaking, a time when Hollywood had largely discarded the sugar-coated schmaltz of ’50s and ’60s artifice.

Galella and his wife share a home in New Jersey where framed photos taken by the two of them vie for attention with a large collection of rabbits: wooden, porcelain, and glass renditions – as well as a few live ones. “They don’t bark and they don’t smell,” Betty explains. Their basement contains a sprawling labyrinth of filing cabinets and shelves where over one million photographs are catalogued. Theme-photo boxes, marked “Hollywood Kiss” or “Smoking”, are squeezed onto shelves that groan with the weight of mammoth Jackie Kennedy and Liz Taylor collections.

Even a brief dip into the archives proves to be an overwhelming venture; the vast array of stars and their milieus is mind-boggling. And it is difficult to find a bad picture. “Most paparazzi are not trained, anyone can pick up a camera and be a paparazzo,” says Galella. “I was an artist before this, so I understand a bit about art, composition, color, and directional lighting.”

One wonders if Jackie were alive today would she have second thoughts about Galella’s work, as her son John-John did when he asked Galella to shoot him for George magazine. Would Jackie still order her Secret Service men to smash his camera, as she did in 1969? “Okay, smash my camera. I’ll get another one,” Galella wrote in Off-Guard. “Because practicing my trade is my right, my duty and my sole ambition in life. And the more I work at this risky game, the more I am convinced it is the only game for the true photo-journalist, for the picture-reporter who is in unafraid pursuit of the truest picture.”

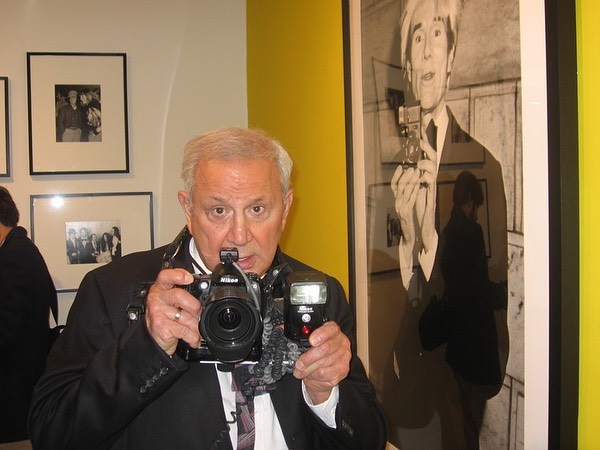

Ron at the opening of his show at Staley-Wise in 2008, to celebrate the release of his Warhol book That’s Great! Photo: Glenn Belverio

Thanks for reading,

Glenn Belverio