Dear Shaded Viewers,

At the end of the 50’s Japan was in trouble. People were not going to the cinema that much. Films started to be made for a younger audience by younger directors. It was the 60’s and the Nouvelle Vague was popular in France with directors like Godard and Truffaut and so Japan had their own Nouvelle Vague with young directors that unlike in France, they never knew each other or worked together. Nagisa Oshima was important in that realm.

With the help of the Shochiku Production Company, Nagisa Oshima had the opportunity to make a film. His first was The Boy Who Kept Pigeons. Afterwards he made another film The Sun’s Burial, this is when violence first entered his films. Shochiku did not make the money they had hoped to earn from them and as Oshima’s films grew more and more political, like Night and Fog, they were steadily losing interest and put Night and Fog in just a few small cinemas in the country and took them out after less than a week. Oshima became furious with them so he left Shochiku and formed his own production company making the kind of films he wanted to do. In the 60’s students were rebelling from France to Japan. When Oshima left Shochiku he was free and could invent new narratives and new ways of making films. His films became more and more pointed and subtle. His first three films showed a concern for young people and their need to revolt. In Night and Fog the subjects were no longer kids they were on their way to some kind of responsibility. The forth film it becomes didactic. Oshima identified himself with the poor people at the bottom. He was famous for shooting on the streets. He, however, came from a monied family. He showed the individuality and those trying to make the best of their lives with their challenges. American films were a big influence in Japan. Before and during WW2 there had been heavy censorship but by the time he was making films that had changed. He was a fan of ‘film noir’ particularly American. He was very influenced by Nicholas Ray and learned a great deal from American pictures. He loved the early films of Godard like Breathless, Renais’s Last Year at Marienbad. His style was very eclectic. He loved fast cutting, strong colors and as time went on his style dissolved into something else. In the beginning he was very close to his subjects and in time he took more of a distance. In the beginning with his films he liked to put his actors in confrontational situations and then sit back and see what happened. Later films he became more respectful to his actors.

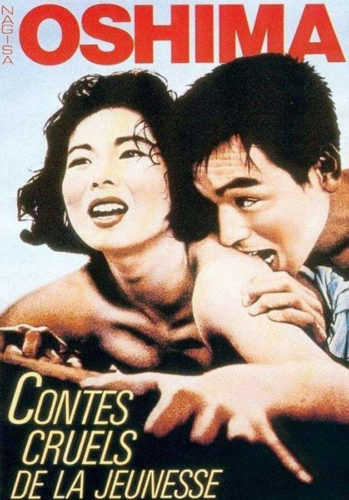

Oshima was 28 when he made the film Cruel Story of Youth which is set in 1960 Japan, restless university student Kyoshi (Yusuke Kawazu) seduces pretty teenager Makoto (Miyuki Kuwanu) and quickly convinces her to take part in a dark, cruel scheme, both to get easy money and to keep their boredom at bay. Kyoshi and Makoto begin preying on middle-aged men, who easily succumb to Makoto’s charms, only to be blackmailed. The couple’s growing frustration with the constricted world around them pushes them into increasingly ruthless behavior.

After Makoto Shinjo hitchhikes a ride, the driver tries to molest her, but is stopped by Kiyoshi Fuji. He takes her on a date, first to watch the Anpo Protests against the US-Japan Security Treaty, and then later to ride a motorboat on a river, where he rapes her. One day, after trying to wait for him at a bar he frequents, she is targeted by gangsters who prostitute women, but Kiyoshi fights them and they leave them alone in exchange for a payment. The two fall in love and Makoto spends more time with him, causing her to be rebuked by her older sister Yuki, resulting in her deciding to live with him. To make money, the two reconstruct how they met, with Makoto seducing a driver and, when he comes on to her, Kiyoshi extorting him. In one case, a politician named Horio picks her up, but makes her feel happy so she doesn’t do it.

When Makoto finds out that she is pregnant, Kiyoshi tells her to get an abortion, but when he tries to get her to exploit a driver again, she refuses. Horio picks her up, and when she calls Kiyoshi to ask whether she can stay the night, the line is busy. Kiyoshi asks an older lover he is seeing for a loan and when he gives the money to Makoto, she tells him she slept with Horio. In response he finds Horio and takes money from him, telling him that he was just another target of Makoto’s. After the abortion, performed illegally at the clinic of Yuki’s former lover Akimoto, the couple is arrested for extortion. After they confess, and with the help of Kiyoshi’s older lover, the two are released and Akimoto is arrested.

Kiyoshi breaks up with Makoto so they won’t hurt each other anymore. The gangsters find Kiyoshi because the motorbike he borrowed from them for the extortions was stolen, resulting in two of them being arrested. They ask him to give them Makoto, but Kiyoshi refuses and is killed. At the same time Makoto is given a ride by a passerby, and when he refuses to let her out, she jumps out of the car to her death.

“The fury of life made in Japan: truly ruthless. Les InrockuptIbLes

“A cry of alarm from a youth without hope” téLérama

“A violent love story to which the dazzling direction guarantees an eternal adolescence” cahIers du cInéma

Vincent Canby of The New York Times complimented the colors and cinematography of the film, but was confused by its unexplained political and social references and felt the story was told too distantly, making it dim.[2] Mary Evans of The Japan Times compared the film to a sociological study which, while mostly succeeding, failed when it moralized. She also found faults in the originality of the story, the violence of the ending, and the portrayal of the gangsters and Makoto, but called the film strong and praised Ōshima’s “great feeling for his medium.”[3] James Hoberman of The Village Voice described the film as a “candy-colored extravaganza [that] is directed with considerable brio and filled with bold metaphors”, but felt that certain aspects were dated such as “powerless men preying upon even weaker women” and its “absence of cynicism and even careerism.”[4]

The film won the 1960 Blue Ribbon Awards for Best Newcomer for Ōshima.[5]

In 1976 he made In the Realm of the Senses about a former prostitute working as a servant and has a torrid affair with her married employer.

Contes Cruels De La Jeunesse made in 1960 is 97 minutes in color and newly restored 4K VO DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0

in Blu-Ray Disc out August 25th

Distributed by Carlotta Films

Later,

Diane