Dear Shaded Viewers,

Very sad to hear about the passing of Daniel Johnston. I wanted to share this feature I wrote about Daniel and his life that appeared in ZOO magazine in the summer of 2005.

Hi, How Are You?

By Glenn Belverio

The Orange Show in downtown Houston, Texas seems an unlikely venue for most performers – unless their brand of music falls into the non- existent category, ‘surrealist blues.’ When Daniel Johnston steps into the small cement arena in the outdoor club’s courtyard – a hodgepodge of eclectic weather vanes, model ships and terraces adorned with brightly painted wagon wheels – it seems he might be the undiscovered genre’s sole member. Shaking terribly due to the medication he takes to subdue his bipolar disorder, Daniel blows his nose, opens a can of Coke and begins strumming his acoustic guitar, singing a new song titled “Love Can Save You Now.”

His voice is off-key – one of his trademarks – an effect that is often alarming before it becomes charming to the uninitiated listener. The audience of mainly Rice University students, clearly initiated, is assembled in the club’s tiered cement seats, sitting in rapt silence and lending a church sermon-seriousness to the proceedings. The club’s power goes out during “Baby, You’re Driving Me Crazy,” and a woman seated behind me, who is older than the gathered students, cries out “Daaaan- iel! Keep going!”

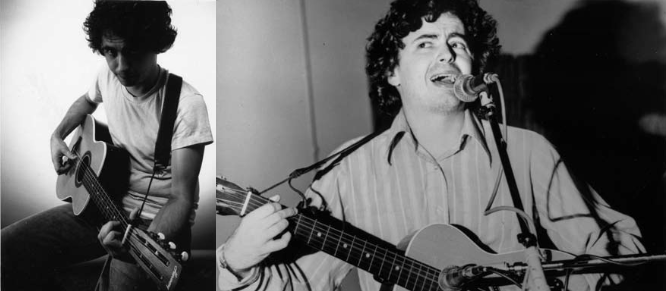

Above: Daniel back in the ’80s

The power goes on and off a few more times, with a few obtrusive belches of feedback in between, and the 44-year old singer finishes the song undeterred before switching from guitar to piano. The woman rocks back and forth and sings along intensely, as if momentarily touched by the Holy Ghost. “No more heartache, no more pain…”

“He’s crazy, he’s fabulous, he’s totally sincere,” the woman, Paula, tells me after the show. Originally from Austin – the Texan city known for its indie music scene and where Daniel made his mark in the early 80s by handing out homemade tapes of his work – Paula is a bit loopy, in a Texan bohemian kind of way. “I knew him back in Austin in the mid- 80s, before he hit his girlfriend but after he threw the woman out the window,” she remarks casually. “And there were those days when the phone would ring – Daniel calling me, wanting to talk. I don’t know him that well now.”

The woman he threw out the window, breaking both her legs… the friend he beat with a lead pipe… the day he caused the plane that his father was flying to crash in a farmer’s field. Delusions of people possessed by Satan, numerous check-ins at mental hospitals, nervous breakdowns, large daily doses of Lithium… I decided to withhold all these tales of Daniel’s troublesome history from my zaftig, African-American driver, Shannon.

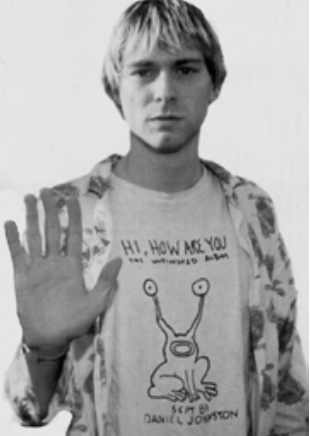

Above: Beautiful Kurt Cobain in his Daniel Johnston t-shirt

A real down-home Texas girl, Shannon regaled me with tales of possum roasts from her childhood as we scarfed down beef barbeque, ribs and corn bread at Luther’s BBQ. Since she was my designated driver from Houston to Daniel’s small hometown of Waller, I didn’t want to needlessly panic her with visions of mid-interview freak-outs and impromptu exorcisms.

“The numbers on their foreheads and hands/The devil has Texas” – “Devil Town”

Daniel greets me at the door of his parent’s two-garage ranch house, wild-eyed and a bit manic, his grey mop-top disheveled. His grey T-shirt is snug around his large, beach ball-size belly. A melancholy song by The Carpenters drifts from a tape player on the dining room table, where a large assortment of crayons and magic markers are neatly arranged in plastic organizers. A black line drawing of Captain America bursting through a sea of human skulls is lying next to a large stack of horror comic books. Daniel asks if I want a glass of Kool-Aid. “Wow, this is just like his song ‘Happy Time,’” I think to myself. (“Kool-Aid flowing like wine/The comic books, the TV shows, the bubblegum, the kitty cat….”)

However, the Kool-Aid never materializes and Daniel already has his sneakers and navy windbreaker on, ready for our trip to the Sonic Burger drive-in. “They brought the drive-in concept back to life,” Daniel enthuses about the venerable fast food chain. “I go there a LOT… with all my friends, my producer, everybody I record with. We sit in the car and shoot the breeze for hours.”

During the ride, Daniel tells me about his favorite flea market, where he goes to buy used comic books and records on the cheap. “It’s called Trader’s Village, over in Houston,” he explains. “Not ‘traitor’ like Judas in the bible, but ‘trader.’” Religious motifs come up a lot in the Daniel Johnston oeuvre, mainly due to his Christian fundamentalist upbringing. They range from the ruefully reverent (“they were playing guitars and getting loud… and they spilled beer on Jesus”), to the heroic (“these are the adventures of God as a young boy… he was the most victorious of the jungle”), to the rebelliously sacrilegious (“Time flies when you’re having fun/Aborted babies are the lucky ones.”)

Some critics have speculated that one of Daniel’s muses, Casper the Friendly Ghost, is an allegory for Christ, in Daniel’s song about the cartoon spirit. (“Nobody treated him nice while he was alive… but everybody respects the dead.”) Daniel is dismissive of this comparison. “I really don’t think so. But Casper was always a good guy, trying to help everybody. That’s how I saw myself. Not really a goody two-shoes, but always trying to be a good guy,” he says, before adding cryptically, “and I was always a ghost.”

Now, whenever Daniel feels inspired to write a song that has a religious theme he puts it aside, saving it for his gospel album project. “Will there be a gospel choir singing on the record?” I ask hopefully as we pull into the parking lot of Sonic Burger. Ignoring me, Daniel falls silent and his face glazes over as the car rolls toward the colorful menu equipped with a speaker for taking orders. I turn off the tape recorder, Shannon looks quizzically into the rearview mirror. I break the awkward silence by commenting on the green apple slushies on the menu. I order one and Daniel comes back for a moment. “Oh, I’ll have one of those, too.” I ask for my cheeseburger without onions, so does Daniel, and after he wolfs it down he falls into what seems like a medication-induced nod.

“It’s so tough just to be alive/When I feel like the living dead” – “Life in Vain”

A severe manic-depressive, Daniel went through extreme periods of creativity that were often followed by dark holes of unproductive depression before he began taking a cocktail of medications. He still has the highs and lows but the medication keeps him more stable. “A truck almost ran me down/Oh I’m not so bad/Please don’t be mad/I’m finding my way, finding my way oh,” he sings on “Almost Got Hit by a Truck.”

Daniel’s songs ache with the sadness and hope of a survivor, of someone who has been to the bottom of the abyss and made it back up, again and again. It’s tempting to compare Daniel’s plight to the sort of American southern madness that inhabits a Tennessee Williams play or to romanticize his mental illness and its arguable link to his music and drawings. You might not be irresponsible or incorrect but you’d be remiss if you didn’t linger over his uniqueness. “We did “Walking the Cow,” which captures a moment where he was cracked up, but knew he had to walk the cow,” says Tunde Adebimpe of TV on the Radio.

His band covered the song for The Late, Great Daniel Johnston, a tribute album released last year. “He focuses totally on this mundane task in the belief it will deliver him to his true love. That’s just heartbreaking.” What is impressive about Daniel’s musical output is that he has written literally hundreds of songs whose lyrical treatment avoids repetition. His central themes – unrequited love for a school crush named Laurie, loneliness, pain, monsters and comic book characters – remain fixed but his approach to them in each song always succeeds in being astonishingly original. And they have a universal appeal. “Daniel’s work is simple enough for anyone to relate to,” says Adebimpe. “But if you have ever felt anything in your life, the words will bore into you.”

During the ride back to his parent’s house, I ask Daniel about the recent documentary that has been made about his life, The Devil and Daniel Johnston, which won the Best Director award at The Sundance Film Festival. “I went to two screenings at Sundance and it was great to get all that attention and audience applause,” Daniel says, feeling a bit more upbeat for a moment. What was it like watching his life on the big screen? “There was nothing I could do about it, they tried their best. Some moments I cringed at.” Which ones? “I don’t want to say”, he says sullenly before adding in a languid, deadpan tone, “but the movie was funny, it was hilarious.”

“The film pulls no punches and Daniel’s family made me promise not to leave anything out because they want to help other families,” says Jeff Feuerzeig, the director of The Devil and Daniel Johnston. “That means when Daniel watches the film, he has to watch himself throw a woman out the window. He has to watch himself crash his Dad’s plane and al- most kill him. He has to watch his Dad cry. Basically, he has to watch a lot of heavy shit.” Before Feuerzeig made the film, he researched the phenomenon of the link between mental illness and creativity, by read- ing books like Touched with Fire. “There’s no question how interlinked manic-depression and creativity are,” he tells me. “Daniel exploited his mental illness, because his music and his art are about his mental ill- ness.”

The film notes that, as of early 2005, 150 artists around the world have covered Daniel Johnston songs. “I think Daniel is one of the finest songwriters around, if not the finest,” says Norman Blake of Teenage Fan Club, whose band covered Daniel’s song “My Life is Starting Over Again.” Jad Fair, a long-time collaborator of Daniel’s, suggested they cover it. “Daniel’s appeal is that he’s never played by the rules,” continues Blake. “And his songs are very honest, sometimes painfully so.”

Back at the house, Daniel shows me a few more of his drawings in the dining room-cum-atelier. “I make ten drawings every day and my dad gives me $10 apiece for them,” Daniel says proudly. Daniel’s dad and his brother Dick then sell the drawings on eBay to fans for a few hundred dollars and put the money in a savings account for Daniel’s future. On Daniel’s website, www.hihowareyou.com – which Daniel rarely sees be- cause neither he nor his parents own a computer – one can log on and read hundreds of messages posted on the fan forums. “Yes he is in a writ- ing slump right now,” reports one poster, who sometimes talks to Daniel on the phone. “But it does not seem to really bother him. He knows it will be back.”

“I never finished anything I ever started/But I think I’m gonna quit being a quitter” – “Lazy”

Daniel takes me into the house’s cavernous kitchen where his 82-year-old mother, Mabel – who suffers from Parkinson’s disease – is holding herself up with a chair while Bill, his rather robust 81-year-old father, is making a sandwich. “Dan’s been around the world, he’s been to Af- rica,” Bill says proudly when I ask about Daniel’s worldwide popularity. A World War II veteran who shot down Japanese fighter planes, Bill ac- companied Daniel to Tokyo 40 years later. “It’s a long flight – 20 hours – and the Japanese treated us royally,” Bill says, politely pretending not to hear me mention the war. “But Daniel sprained his ankle really bad and had the gout the last day we were there.”

“Yeah, but I had three geisha girls massaging my back backstage at my show”, Daniel says gleefully, with a hint of mischief in his eyes. “It was heaven!”

Bill’s strict Christian father side emerges. “Oh Daniel, come on! That didn’t happen!” he scolds. “Did it really happen?” I ask Daniel, fanning the flames a bit. For a moment I swear I hear the faint crackle and pop of brimstone in the nearby microwave. Daniel starts rubbing his stomach maniacally. “I was like ‘Ooooh, ooooh, yeah!’ It was gooood, man!” Bill frowns at me, I change the subject. “And what happened in Africa?”

“We were invited to South Africa to do the filming of the ‘King Kong’ opera thing,” Bill says, referring to one of Daniel’s more well-known songs. “But it turned out kind of disappointing.”

“It was a lot of fun filming that. I had on a gorilla suit and I was jumping around and growling,”says Daniel.“But the final film was just me sitting there reading the song.”

“And he climbed up and looked around… Just him and his screaming woman/They were finally alone”- “King Kong”

Daniel takes me to his studio, which is housed in one of his parents’ garages. The studio is an eBay bidder’s wet dream; a treasure trove of toys, monster figurines, vintage posters, magazines, records and books. It’s difficult to move around in the studio for fear of toppling a mummy model or a Ringo Starr doll. A Navajo swastika flag is draped over the chair next to the piano where Daniel composes his songs. “I come out here every day and work on music,” Daniel tells me. “I start pounding out some chords and write whatever comes to mind. But most of the time I like to watch monster movie DVDs.”

On the wall behind him is a giant King Kong poster hanging next to another for Head, a film from the 60s that starred The Monkees. I mention that it is one of my favorite films and Daniel starts frantically rubbing his belly again. “The Monkees TV show was so excellent and I swear that Salvador Dali filmed some of the episodes,” he says emphatically. “It was great art.” Behind me I notice a painting that Daniel has done of the Beatles – who he has been obsessed with since childhood – with a fifth member added. “It’s supposed to be me but it came out looking like Charlie Chaplin,” he says sullenly.

I can tell that Daniel is growing tired of the interview and wants to get back to his monster movies. He tells me his current favorite is the 50s film, The Creature Walks Among Us, whose plot concerns the Creature from the Black Lagoon being turned into an air-breathing semi-human by a mad scientist. Unhappy with his new condition, the creature escapes and goes on a killing spree. “At the end of the film he goes back into the water and commits suicide,” Daniel says, taking a drag from a cigarette and looking down at the floor. “The poor monster… it’s kind of sad.”