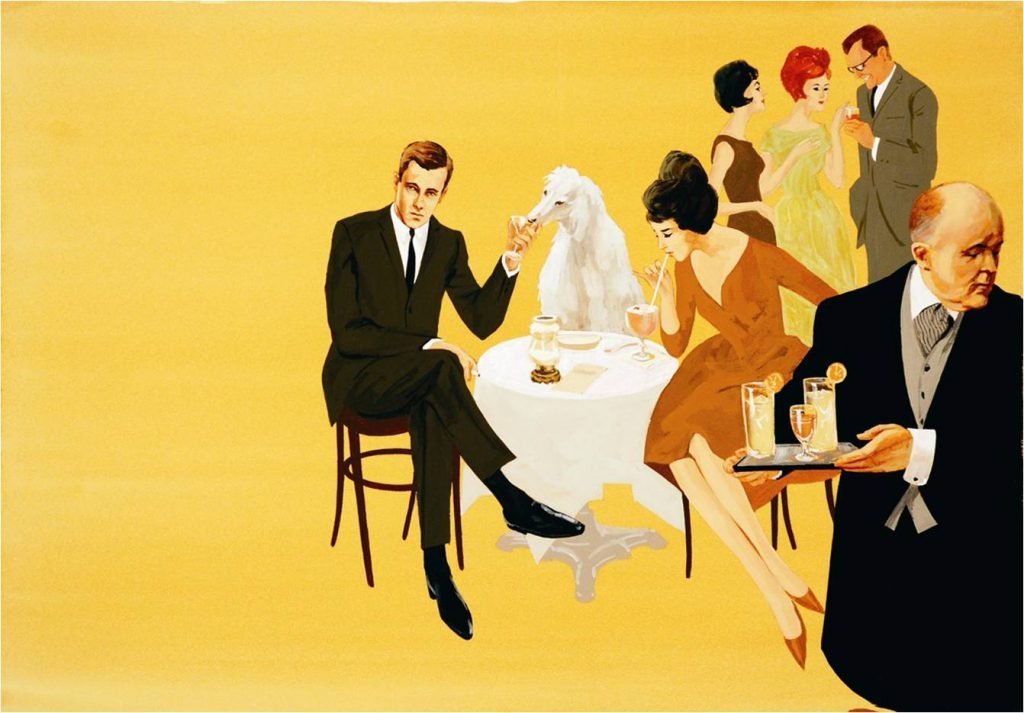

Above: 1. Larry Salk (American, 1936-2004); Illustration, Summer Cocktail Party with English Butler, 1961; Watercolor, gouache, ink; Collection of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf. “This illustration so beautifully captures cocktail culture of the post World War II era in which both the clothes, and the cocktails are gendered – his more serious martini paired with his sober suit, and her Pink Lady paired with her overtly feminine New Look dress.” 2. A clip from the 1928 silent film Our Dancing Daughters starring Joan Crawford

Dear Shaded Viewer,

Regarding my favorite sport—drinking—I think Frank Sinatra said it best: “I feel bad for people who don’t drink. When they wake up in the morning, that’s as good as they’re going to feel all day.”

Last week, at the gorgeous National Arts Club on Gramercy Park in New York City, we took a deep dive into the history of imbibing with an engaging lecture and slideshow (with film clips!) by Michelle Tolini Finamore, Curator of Fashion Arts at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, entitled Cocktail Culture and Couture.

After the lecture, I interviewed Michelle about what is one of my all-time favorite topics.

Glenn Belverio: When did you first become interested in cocktail culture and how did the Cocktail Culture & Couture exhibition come together?

Michelle Tolini Finamore: I am a fashion historian who loves to drink cocktails! While I was working part-time at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston I was asked to curate the “Cocktail Culture” exhibition at the Norton Museum of Art in Palm Beach. Seeing that it blended two passions, I jumped at the opportunity. I have always been interested in how fashion reflects social and aesthetic changes and any other medium, including the cocktail, can be viewed through the same lens. So diving into the history of the cocktail it soon became clear that the titles, the ingredients, the objects, and the clothing associated with cocktail drinking had a story of their own that was worth telling.

GB: In your lecture, you traced the history of early cocktail culture, something that is purely an American phenomenon. In fact, it’s taken Europe a century to catch up with it. For the longest time, a “martini” in Spain or France or Italy just meant some dry or sweet vermouth on the rocks. And then, just a few years ago, an American-style Martini bar popped up across from the Tuileries in Paris. Not too long ago, attempts at cocktail-making by bartenders in Berlin was a disastrous affair. Now there are all kinds of bars mixing up superior cocktails there. Why do you think it took America to invent and perfect the cocktail? What were some of the social and political circumstances that helped shape cocktail culture?

MTF: You are so right! The scene in Europe definitely seems to be changing – I was so surprised that I could get fully evolved cocktails on a recent trip to Italy. Not that I don’t love an Aperol spritz, but every now and then I really crave a good Whiskey Sour or an Old Fashioned. As for why the cocktail is a uniquely American phenomenon, and the answer is multi-faceted. America has always been a country that strives to erase social and class boundaries, and that is nowhere more evident than in the entertainment spaces that developed over the course of the 20th century.

Bars, tea salons, speakeasies, and nightclubs where people of all backgrounds could intermingle became part of the social fabric. America takes pride in its history as a melting pot and I am fascinated that the history of its cocktails reflects diverse ethnic and regional influences. And, ironically, I think Prohibition (1920-1933) had perhaps the most profound effect on cocktail culture. Cocktails took on the frisson of the forbidden, adding to both their allure and glamour. That thirteen year period is responsible for the great flowering of experimentation in mixology (to hide the taste of the bootleg gin!), an explosion of varied cocktail shaker forms and paraphernalia, and a very specific, and fashionable, culture associated with drinking.

Harry Craddock (American); illustrator Gilbert Rumbold (English, active 1920s-1950s)

The Savoy Cocktail Book, 1930

Constable and Company Publishers

Private collector

MTF: In 1920, famed mixologist Harry Craddock left the United States, claiming that he was “exiled by Prohibition.” By 1925 he was the head bartender at the American Bar in London’s Savoy Hotel and was instrumental in the introduction of American cocktails to Britain and Europe. Craddock mixed drinks at the hotel until 1939 and his Savoy Cocktail Book is still one of the standard references in the field.

GB: I really loved in your lecture the way you talked about the early connection between women’s independence and cocktail culture—and how you presented Joan Crawford (my favorite actress) as the consummate flapper who exemplified the new social freedoms that women were experiencing (in Our Dancing Daughters). In fact, one of my favorite cocktail film scenes is from Grand Hotel, when a young Crawford glides up to the bar and breezily orders an absinthe. Can you talk a little bit about how cocktail culture helped shape the identity of the modern 20th-century woman?

MTF: Women’s newfound independence in the early 20th century had a dramatic effect on the acceptance of women drinking, and, importantly, gaining entrée into the formerly male-dominated world of cocktail consumption. Moving into the workplace, gaining the right to vote in 1920, and other such freedoms all contributed to the idea that, unlike the 19th century, women were in control of their destiny. And their very clothing and accessories reflected this – consider the 1920s flapper in her liberated, corsetless dress, going to a nightclub, listening to high energy jazz, dancing, and looking into her compact to apply her make-up.

When Crawford in Our Dancing Daughters is asked to make a toast she dedicates it “To myself” – this is a woman who is confident and in command of her own image-making. In addition, if cocktails were only to be consumed in more masculine bars or clubs, the culture never would have taken on that glamorous patina with which it was eventually associated – we need women in their beautiful dresses for that!

Some Smoke Music Sheet, c. 1905

Published by JLS W. Stern & Co.

Collection of Jimmy Raye

MTF: Although women were not commonly seen in drinking establishments until the 1920s, the idea of women participating in this formerly male domain was becoming more acceptable by the turn of the twentieth century. This music sheet, with tunes for the dances like the turkey trot, depicts the “New Woman” in her Art Nouveau-inspired finery, sitting at a bar, and smoking – activities that would have been unacceptable for the Victorian era woman.

GB: It was nice to see in your slideshow some of those archival Tiffany & Co. Blue Book jewels (I think I mentioned that I collaborated on the copy for Blue Book for three years) paired with cocktail recipes, etc. And those early Tiffany cocktail accessories, like the vermouth “oil can” (which they still sell). Besides the recipes and the imbibing and, of course, the clothing (which we will get to), there was a whole world of design objects orbiting around cocktail culture, from the elite (the jewels, crystal and sterling barware) to the populist (mass-produced aluminum cocktail shakers, Playboy bunny swizzle sticks). How did you go about choosing objects for your exhibition at the Norton Museum of Art?

MTF: It was very difficult to hone down the list! There really was so much to choose from, but ultimately I tried to exhibit what I thought was the best of the best. You always start with you ideal object to represent any given moment in time – for example the majestic 1940 World’s Fair moonstone-adorned shaker and cups by Tiffany for the World’s Fair and hope you can find it. Tiffany was a natural because the company has such a deeply-rooted tradition of craft and represents a uniquely American aesthetic.

Then you fill in…one collector had the most incredible array of cocktail shakers in private hands that I have ever seen and I chose based on a variety of forms and the quality of craftsmanship. I also had a very short time frame to organize the exhibition so I tried to focus in on a few key collections that would offer a number of objects…Lillian Bassman photography from her archive, works from the MFA with which I was familiar, and then filled in accessories from one private collector of vintage fashion who happens to live around the corner from me.

D.R.G.M. (German)

Monoplane portable bar set, c. 1930

Silver plated metal

Collection of Beth Rudin DeWoody

MTF: The 1930s witnessed an explosion of creativity in cocktail shaker forms, including this imaginative bar-in-one, which includes shaker, hip flasks, strainer, cups, spoon, corkscrew and funnel contained within the form of a monoplane.

GB: The Edith Head brown gros de Londres gown that a Martini-fueled Bette Davis wears as she goes bounding down the stairs to the cocktail party she is hosting (“a night to go down in history”) in All About Eve is one of my favorite dresses in the history of cinema. Can you talk a bit about your favorite pieces that you included in your lecture and exhibition?

MTF: This Lanvin ensemble (below) is the quintessential 1930s cocktail “dress” in its unusual harem pant styling and shimmering surfaces. Parisian couturier Paul Poiret (French, 1879-1944) introduced women’s harem pants as early as the 1910s, but they were not readily accepted by mainstream wearers. By the late 1930s, women were more comfortable asserting their independence and actively participating in cocktail culture. The design, which was featured in both Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, cunningly refers to the exoticism of the East as well as women’s ever-increasing emancipation.

Jeanne Lanvin (French, 1867-1946)

Evening ensemble, winter 1935-1936

Silk plain-weave crepe, gilt leather

Collection of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of Miss Lucy T. Aldrich

GB: Finally, I would be remiss if I did not ask you what your favorite cocktail is, and why.

MTF: It is hard to choose a favorite because I have tried so many over the course of my “research.” But one of my standards is a Whiskey Sour done the right way and not too sweet – lemon juice, simple syrup, egg white, and good quality whiskey or rye. And another favorite – one that I mentioned in the talk is the Corpse Reviver #2 for its complexity. And lastly, one that my husband invented that is a mixture of rye, gin, Benedictine, Maraschino Luxardo, Peychauds Bitters, and a twist of lemon. As we were trying to concoct a name for the drink, we kept getting interrupted by my children…hence the name: “Why do I bother speaking?”

Some party shots from that evening at The National Arts Club:

My date for the evening, Studio 54 legend Snoogy Brown, and Jean of Idiosyncratic Fashionistas

Thanks for reading.

xxx

Glenn Belverio