The Top Secret exhibition explores the intertwined relationship between espionage and cinema, reflecting the breadth and vitality of a subject that unfolds as much in a history as in a global geography. The epicentre of espionage intrigues is constantly being shifted and reconfigured, from the divided cities of Europe (The Kremlin Letter, John Huston, 1970) to the Middle East (the Bureau of Legends series, created by Eric Rochant), today highlighting renewed intelligence strategies, characteristic of the post-September 11 security world, whose impact on the mise en scène generates new codes and new faces.

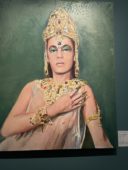

Resisting stereotypes, the Top Secret exhibition deconstructs the sexist representation of female spies, long relegated to the sole practice of the “Honey Trap”, and re-establishes their considerable strategic contribution, which the cinema was able to do justice to early on. From Protéa, a Jiu-Jitsu enthusiast and the first spy in the history of cinema (1913), to Mata Hari, shot for intelligence with the German enemy (played in 1931 by Greta Garbo, later immortalized in this role by Andy Warhol), cinema has been interested in the figures of female secret agents from the very beginning: Marthe Richard and Mademoiselle Docteur are heroines whose adventures on the big screen are based on real events, while Alicia Huberman (played by Ingrid Bergman) in Les Enchaînés (1946) embodies, in front of the camera of Alfred Hitchcock (the undisputed master of ten major films on espionage), a fictional fantasy of a courageous undercover woman. In addition, many stars took advantage of their fame to join the intelligence services out of patriotism: Marlene Dietrich, as Agent X27 in Josef von Sternberg’s 1931 film, spied on a few Nazi dignitaries for the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS). The risks taken by these actresses (such as Hedy Lamarr, the originator of the future GPS, and whose multiple facets have been explored in sculpture by the artist Nina Childress) make it possible to re-evaluate the importance of women in the art of intelligence and bear witness, by comparison, to the way in which some have long distorted this commitment, by favouring the hypersexualisation of sexpionage

UNDERCOVER

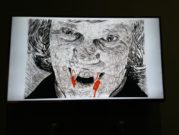

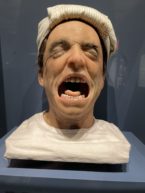

Spycraft is no more reducible to a genre than it is to an artistic medium: always seeking to reinvent itself, it moves from literature to cinema (many of the films shown in the exhibition are adaptations of books by Ian Fleming, Graham Greene or Tom Clancy), and from design to contemporary art. The exhibition thus orchestrates visual proposals, playful or sometimes deliberately disturbing, by the Canadian Rodney Graham, the Ukrainian Boris Mikhaïlov, the Frenchman Julien Prévieux, the Serbian Nemanja Nikolič, the Lebanese Walid Raad (The Atlas Group), or the American Heather Dewey-Hagborg, who question cryptology, simulacra, and even brainwashing through their works of art. These are all mysterious and fascinating themes that make the spy the romantic character par excellence, the receptacle of filmmakers’ fantasies. Capable of slipping from one identity to another, the spy never ceases to conceal himself and to dress up like an actor with extraordinary talents. Sometimes invincible, sometimes tortured, he haunts auteur films (Secret Conversation, Francis F. Coppola, Palme d’Or in 1974) as much as B movies (One Spy Too Many, Don Siegel, 1977); humorous comedies (Modesty Blaise, Joseph Losey, 1966) as well as committed thrillers (Spies on the Thames, Fritz Lang, 1944). His popular aura peaked in the 1960s, when Cold War tensions (that secret world war) were at their highest. Western spy films responded to the diplomatic opposition between the two blocs with propaganda that did not hesitate to praise individual freedom and the opulence of consumer goods. However, John le Carré, a former spy in the British MI6 and now a famous writer, does not hesitate to show that this summary Manichaeism reflects the interdependence between the spy and the spied, between the West and the East, replaying the dialectic of master and slave. Situating his plots on both sides of the Wall, the writer has always documented the Communist state secrets with precision, before reinventing them in fiction. In The Mole (published in 1974 and adapted for the cinema by Tomas Alfredson in 2011), he imagined the Soviet agent Karla, modelled on the implacable Markus Wolf, director of external intelligence for the Stasi. One of the peculiarities of the Cold War was the constant dialogue, through fiction, between East and West, who came to learn about the mindset and technological advances of the enemy camp through film.

ON LISTEN

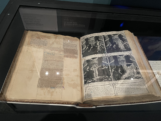

Top Secret also accompanies the very serious march of History, and exposes the role of cinema as an instrument of propaganda or spy training. Because the recording of reality is a necessary art for the secret agent, the techniques of cinematographic capture are at the heart of espionage practices. Cinema and espionage thus share the art – and the technique – of producing sounds and images, which are then arranged to form a narrative. The heart of this common territory consists of the many high-performance devices used to accomplish their tasks: cameras, Nagra, microphones, etc., all of which help to follow one person and to film the other. The exhibition will show rare originals, some of which date back to the 19th century.

But at the beginning of the 21st century, anyone can use a simple mobile phone to collect or hack into sensitive information, while thwarting state surveillance systems. You don’t have to be a stunt superhero like Mission Impossible (series and films, 1966-2017) to do this. A more minority of committed cinema bears witness to these new practices, setting up as fictional leader the geek Jason Bourne, played by Matt Damon in the five films of the saga inaugurated by Memory in the Skin in 2002. A former CIA agent turned renegade, he is the embodiment of the contemporary lone vigilante who challenges the new masters of the world in handheld action scenes. In reality, these models can be found in the form of citizen-spies Edward Snowden or Chelsea Manning, who choose to share top-secret information on camera in real time (Citizenfour, directed by the activist Laura Poitras, Oscar for best documentary, 2014). Today, these investigative practices are also claimed by committed artists: this is the case of Trevor Paglen whose telescopic photographs highlight the illicit surveillance activities perpetrated by the USA. In this new millennium, when some thought that espionage had been relegated to hilarious parodies a la OSS, the opposition between the new forces in power demonstrates how the art of intelligence is more topical than ever, raising ethical and political questions, while producing new artistic and critical forms.

Alexandra Midal & Matthieu Orléan, curators of the exhibition

https://www.cinematheque.fr/exposition.html

51 Rue de Bercy, 75012 Paris