Dear Diane and shaded readers,

I recently re-encountered past Munich Art School buddy, Yuka Oyama, we both studied contemporary jewellery and metal-smithing (Schmuck und Gerät with Prof. Otto Künzli, now known as the SCHMUCK KLASSE led by Prof. Karen Pontoppidan). Yuka is a Japanese-German artist based between Berlin and Gothenburg, where she´s Professor of Jewellery Art at HDK-Valand. Yuka´s work is cross-cutting formats from wearable sculpture to jewellery, to video, photography, experimental choreography, performance and public interventions in common space. Her critical costumes allow her to set stages where wearers play and share personal secrets, these costumes also assist to form a temporary community of viewers/participants and wearers, who come from a variety of backgrounds, age groups and vocations. Yuka explores the costume medium through body-centric devices she makes, these blow up appendages attempt to recover the eroded sense of belonging, identity/self and home. Like myself and many artistic entrepreneurs today, Yuka lives quite a transient life between countries including; Japan, Malaysia, Indonesia, USA and Germany. She also commutes between cities on a regular basis, working as an artist and academic, juggling multiple tasks simultaneously, which is quite a common situation for many in the creative industries today.

Figure 1. Yuka Oyama, Survivaball Home Suits (2020). Photo by Zoe Tempest

AML: We know each from Munich Art Academy days, in the early 90s……how do you go from doing conceptual jewellery design to making theatrical inflatable appendages for the body to perform in a gaming environment? Something I also did, jumping from making pretty wild conceptual jewellery to going on to be a performer in art band Chicks on Speed, we definitely share this in common.

YO: I started out as a studio jewellery artist, at some point I felt constrained by the size and materials that are regarded conventional to jewellery. I was always convinced I wasn’t a jeweller, whenever I started designing forms, I always got stuck, because I couldn’t justify why I should transform the ideas into physical pieces of jewellery. At some point, I came to the realisation that I wanted to make larger sculptures and spatial installations, I went off studying Jewellery and took up a Sculpture MFA and what I’d learnt in Jewellery (with its close connection to the body and semiotics) bled naturally into my sculpture work.

During that time, I discovered that my art requires a human body as part of its expression. I base my thinking on people, matters and feelings that stem from our (or my) everyday life experiences. It’s important for me to express issues that are close to life and to people, which for me is the most direct way to employ the human body, by putting art objects on them, to express or represent their internal worlds. That’s how I came to make wearable art objects of various sizes–from miniature jewellery to life-size sculptures. In time, my ambitions grew further and I embarked on creating narrative stories for my performances, which led me to the creation of critical costumes, that afforded wearers to enact their emotions through their costumes motions. The more I worked this way, the more I understood that my subjects were not just the background to carry or put my sculptures on, they were the living forces embodying the meanings behind my wearable art objects. My body-centric sculptures were informing and transforming the wearers experiences, and the wearers were also transforming my sculptures by animating them. So, I got really into investigating the artistic expressions consisting of person-thing-hybrid and physical/psychological relationships between subjects and (adorned) things.

I especially love how my critical costumes empower my actors to improvise, where odd transactions can take place that are too absurd to be true. Many themes I work on are quite traumatic and these sad stories have aspired me to challenge myself to depict and transform the sadness into unreal–to–be–true humour, one could say they’re a kind of assistive art therapy.

Figure 2. Yuka Oyama, SurvivaBall Home Suits interview process (2020). Photograph: Yuka Oyama

AML: Your personal artistic research method surveys the habits of people, working very closely with your subjects, some of whom perhaps didn’t have a home and so you made them homes. Could you expand on your artistic research methodologies you undertook and the inflatables art production you made as a result?

YO: As I’ve been commuting across countries over many years, I became interested in the things that I always carry with me, a kind of portable property that goes with me to these places. I built up emotional relationships with these items–my personal constants, must haves that we take with us everywhere, I use these ideas in the work I create……everyone has attachments to physical material cultures, things they take with them on their life’s journey.

Like you, Alex, you’ve been moving around a lot. So, you´ve been confronted so often which objects you take with you to the next location. Why does it have to be the shoes, the lipstick, the mascot? How have these personal objects become must-haves? How can they help making anyplace one’s home? In a time when we are settling into new life surroundings and feeling unsure of ourselves, how would these handful of constants remind us and help us to get back the base–self? So, these items hold keys to understand how we make feelings explicit; of home, feeling safe, protected, and grounded.

Figure 3. Yuka Oyama, SurviaBal Home Suits work in progress (2020), work in progress. Photograph: Yuka Oyama

AML: How would you describe your current practice based process?

YO: I always start my artworks with conducting qualitative interviews with protagonists, who share similar life experiences, like living between many parallel homes. I ask questions pertaining to their personal biographies like; why do you carry around these items; object histories; what constitutes the feelings of home, if you’re constantly moving around? As the topics that are related to home, self, and sense of belonging are very personal and not necessarily pleasant themes to speak about, it helps me to divert our attention to portable home objects when I speak to people, so they can have an objectivity.

Figure 4. Yuka Oyama, SurvivaBall Home Suits performance view (2020). Photograph: Zoe Tempest

I’m currently working on the artistic research theme The Power of Small Things that comprises of four artworks. The first one I undertook in New Zealand in cooperation with the Dowse Art Museum, where I interviewed people who experienced migrations either voluntarily or involuntarily and moved around multiple times–in some cases up to 12 times a year! In the second volume, I worked with people who were vocational commuters who worked across cities and countries like myself, expats, pilots, truck drivers, etc., together with the students from Design School Kolding. The insights gained from the artistic research found their way into an artistic production, which was presented at the Milan Design Week, 2018. In the third volume, I worked with children who were growing up or raised in double households–a 50/50 joint physical custody. This work is currently on show in “Look! Revelations on Art and Fashion” curated by Friederike Fast, Marta Herfeld Museum, Germany (September 4, 2021 – March 6, 2022).

Figure 5. Yuka Oyama, SurvivaBall Home Suits – White (2020), plastic, PE Sponge. Photograph: Zoe Tempest

The large-scale installation exhibited at Marta is made up of a series of body centric inflatable sculptures, I see it representative of my life story. It’s a story about children who travel between two homes quite often due to the parents’ divorce. My son lives in double households, splitting his life 50/50. It really mattered to me, how to understand a child’s perspective, what its like to experience living between double households? How do they define home? Do they have two places in mind, or is there just one continuing home space for them? What are the roles of things that travel with them? I conducted qualitative interviews with 30 youths and children as I wanted to have a broader understanding of not just my own child’s experience but of a wider group of children, as I saw it wasn’t just an isolated experience and perhaps what I learnt in my artistic research could help other children and parents.

After undertaking interviews, I understood that the portable constants are both functional and emotional objects. Firstly, they are charged with personal memories, secondly, they often symbolise personal relationships to someone special and thirdly, these items allow the owners to perform things that you do at home in spite of dislocation, like home activities such as; relaxing, running, reading, cooking, thinking, listening to the music, etc. That’s why they become so important, and they can make any place one’s home for the owner. I became inspired by the idea that objects and performance (or rituals) can create feelings of home.

Do you know The Yes Men, Alex?

AML: The Yes Men? Yeah, I love their work and we lectured at similar events on a couple of occasions.

YO: They made a costume called “SurvivalBall” which is supposed to save people from any natural catastrophes, so I entitled my work “SurvivaBall Home Suits” that should protect youths from the situation of switching homes. I wanted to protect them from bumps. I wanted to connect the air of their two homes so that one constant air flows around them and their traveling items are shaping the form of continuous home spaces.

AML: What about the designs how did they develop? Were they co-designing with you?

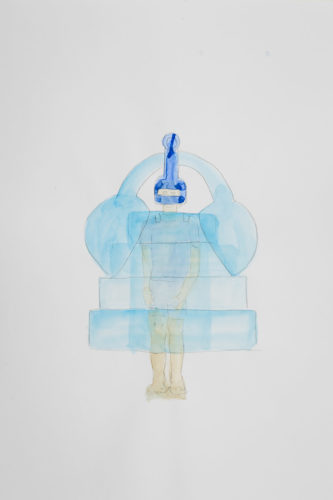

Figure 6. Yuka Oyama, Sketch-White (2020), water colour on paper, 21 x 30 cm.

YO: After conducting interviews, I proceeded to create a watercolour sketch to summarise our conversations–like taking notes, a kind of visual recording. As a token for the interviewees’ time, I always gave them a digital copy of my sketch. Continuing on, I selected seven young people to work with me. I contacted them and said that I was interested in making costumes for them based on their personal stories (telling them I’d start making them only if they could join the performance) those who agreed then became the performers of this piece. I transformed my drawings into inflatables produced by the expert Mr. Mayer in Hessen. I always shared production process images with my interviewees and at the first rehearsal, the youths finally met their critical costumes, which was a magical and moving moment! They all looked really thrilled!

Figure 7. Yuka Oyama, SurvivaBall Home Suits – Pink (2020), plastic, PE Sponge. Photograph: Zoe Tempest

AML: And how did they feel moving around this game environment, how did the game unfold, were there rules?

YO: They told me that they felt like figures wearing the costumes and that they couldn’t move freely and felt quite large. Yes, the game is like a Life Game, you throw a dice (actually two of them). If you land on the numbers, you draw a card called an “Action Card”; it tells you to answer some questions like “How important is your toothbrush? Tell me stories about your toothbrush. Swap your place with the person who’s wearing a red costume”, I got the game idea from a public speech training game app, http://www.rhetoricgame.com/. It inspired me to speak about personal truths spontaneously with disguised appearances like protections.

Figure 8. Yuka Oyama, SurvivaBall Home Suits performance view (2020). Photograph: Yuka Oyama

AML: Obviously your work goes far beyond the role of the artist, you’re an educator and curator, where you worked on the Critical Costume conference and exhibition 2020: Costume Agency. The event was a massive milestone for the diverse artists and theorists working within the field of costume. Could you tell a little bit about your work to put together the exhibition?

YO: To clarify the credits; Costume Agency is an artistic research project led by Christina Lindgren and Sodja Lotker. I worked on curating parts of the online exhibition (not the conference), Costume Agency, my role was artistic director for creating the website and PR for the exhibition. As a curator of the Costume Agency online exhibition, I aimed to highlight the conceptual and critical voices of the costumes. I also wanted to break away from the conventional way of displaying costumes on showroom dummies, to present costumes as living entities carrying agency, so I was clear about the importance of showing live performances or video in tandem with the costumes themselves.

We made an open call, to which 200 people responded, it was really eye-opening! I felt a kind of new wind blowing from a massive distributed critical costume community. The applications came from purely trans-disciplinary artistic fields; theatre costume designers, fashion designers, fine artists, performance artists, choreographers, architects, etc. Many of the artworks dealt with something sensual, emotional, bodily, sexual–full of honest feelings, intuitions, animal-like instincts, charged libido, bold, and fun. These critical costume artworks really had something vibrant, playful, and experimental about them–sort of like an out-cry!

Figure 9. Yuka Oyama, SurvivaBall Home Suits – Green (2020), plastic, PE Sponge. Photograph: Zoe Tempest

AML: I´m excited about this hyper cross cutting body-centric work thats going on right now, actually a lot of it is really coming out of the art schools, like in your art school or mine, Trondheim Academy of Fine Art or the computational arts dept at Goldsmiths, LASALLE, Singapore and Institute of Fashion Design HGK/FHNW Basel, where you have art students working in blended environments, VR, NFT´s and beyond. Like you’re teaching jewellery, but jewellery is not what you make, you’re not really teaching jewellery anymore, because that was something of the 80s maybe, or the 90s when there was this art craft debate going on.

YO: Yes. Although I don’t make jewellery, I’m teaching jewellery and leading the Jewellery Art department. I was trained as a jeweller in the BA and went on to work as an apprentice for a goldsmith in Germany for two years, so I know the traditional jewellery-making skills very well. I’m also familiar with the debate and history in the field of Contemporary Jewellery Art. My colleagues at the university are jewellers, so, my role is to strengthen the conceptual part, so I try to make our jewellery approach accessible for a broader audience and at the same time advocate my students to think consciously of the maker-the wearer-the audience-our society ties.

AML: Oh, very interesting, because if we think about jewellery, I mean today jewellery is so many things! I mean Lisa Walker, Karl Fritsch, or yourself, it’s more about a questioning of value and the role of the object in society and spurring on societal change. In Chicks on Speed we make body centric OBJEKTINSTRUMENTS and some of those things are jewellery actually, but some of them are simultaneously musical instruments (like the high heeled shoe guitar). So, I think that’s very interesting for the field of jewellery that it’s no longer restricted to this miniature precious metal heirloom, collectable asset thing. I had the same feeling as you back then, I always felt restricted by the size of jewellery and the time it took to make something, It really lacked spontaneity, somehow to be able to work and make mistakes and embrace that process live was a challenge for me, i suppose performance is much more in-tune with fast pop and improvisation, which is where I am now, but I love to look at jewellery made by all my art jewellery friends, though I find it hard to wear for longer than a performance, it really marks one semiotically.

YO: I agree. I felt like it’s repetition of the same practice, much about formal explorations. If you use inexpensive, unconventional and alternative materials to make jewellery, that’s considered “contemporary,” which I think is no longer relevant. Recently, a new movement started in Australia and New Zealand among jewellers, who started to examine the concept of ‘live jewellery.’ This term was introduced by a writer Kevin Murray, who assumes that the term was coined by two Australian street jewellery artists, Melissa Cameron and Caz Guiney, according to Murray, ‘live jewellery’ investigates “how jewellery operates in everyday life”, which includes the performative capacity of jewellery: how does jewellery take an active role to establish relationships between people–between the maker, the wearer/owner and the audience? This is really exciting to see jewellery as actants, not just as a passive commodity. I’m excited about this new developments in the field of Jewellery, but I’m also challenged by how to keep the traditional craft skills and knowledge from disappearing, It´d be terrible, if this hands on-craft knowledge would disappear.

AML: Yeah i totally agree, so a question for you. Who would you say are some of the protagonists of this new live-jewellery zeitgeist? I love that! I feel part of it already!

YO: Susan Cohn, Roseanne Bartley, who are both from Melbourne, Australia and Lisa Walker, who’s based in Wellington, New Zealand. Su san´s work has a very strong political core and spreads across jewellery, to design, to performance to fine art. She´s one generation older than I, so I´m not sure if it is appropriate to mention her as the new, but I really admire her art.

AML: Yes, I know Su san, a legend and personal inspiration, I used to work for Cohn as a 19–year–old RMIT Jewellery and metal-smithing graduate, as her apprentice at workshop 3000, which is still going strong and we see each other when she comes to Europe for exhibitions and AiR´s, I studied with Roseanne in the gold and silversmithing dept, RMIT, so great to see what she´s up to. I agree Lisa is a wonderful artist, it comes so naturally for her to channel timely societal issues into her work, we´ve collaborated together since Munich Art School days (for around 26 years), she was the 4th Chick on Speed (thats a secret). I just received a tea-towel from her, picturing her solo show “She wants to go to her bedroom, but she can´t be bothered” her body with all of this stuff on top of it, i treasure that jewel of a tea-towel. She’s so on point, if you think about the circular economy versus the linear economy and sustainability. She totally gets it, the question of being an artist today, what do you bring into the world? How long does that object last?……she’s inventing the circular aesthetics associated with that. This is really what we should all be doing now as artists, reinventing what these aesthetics are that accompany this circularity. I think it’s time.

AML: Thank you, Yuka for this interview and for joining Diane´s ASVOFF 13 as a member of the jury of my curated selection “Fashion Moves”.